music art film review - REDEFINE magazine

Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) 2013: Mid-Point Review of Best & Worst Films

The African Cypher (South Africa)

Directed by Bryan Little

* TOP PICK *

Films like The African Cypher showcase what is so great about festivals like SIFF. This documentary takes a long, sweeping look at the different street dance styles across South Africa, where dancing isn’t just something people to do for fun, but something people to do to live. Director Bryan Little takes a backseat and lets his story tell itself through captivating dance sequences and enlightening interviews, as his subjects go from the confines of their neighborhoods to compete with the best at the “Big Dance Competition”. Although The African Cypher‘s run has already passed at SIFF, mark it down as a film to place on hold at the library in the near future — if anything, for the jaw-dropping dance sequences Little captured forever on film. - Peter Woodburn

Cockneys vs. Zombies (United Kingdom)

Directed by Matthias Hoene

In Cockneys vs. Zombies, a group finds themselves holed up in an East London nursing home with nowhere to go. The similarities to Shaun of the Dead are easy to make, because both films are zombie-comedies taking place in England… but while Cockneys vs. Zombies is nowhere near as good as its predecessor, its cracks at football hooligans and zombie-walking speeds make for some hilarious television, and something worth adding to the repertoire of zombie aficionados everywhere. - Peter Woodburn

June 8th, 2013 – 11:55pm @ The Egyptian Theatre

June 9th, 2013 – 8:30pm @ The Kirkland Performance Center

The Cleaner – El Limpiador (Peru)

Directed by Adrian Saba

The Cleaner features fantastic performances, in the story of a forensic cleaner Eusebio (Victor Prada) who stumbles across an eight-year-old boy Joaquin (Adrian Du Bois) with nowhere to go. Set in Peru as a mysterious epidemic has people dropping like flies, Eusebio goes about his daily routine of cleaning up after those who have perished, while building a life-long connection with someone he doesn’t even want around in the first place. Director Adrian Saba uses restraint perfectly in the film and lets Prada and Du Bois do all the hard work. The setting, although a powerful idea, is just that — a setting. The real heart of the story is the power of hope to shine through in dystopian times. - Peter Woodburn

June 5, 2013 – 9:30PM – AMC Pacific Place 11

June 7, 2013 – 4:30PM – Harvard Exit Theater

Computer Chess (United States)

Directed by Andrew Bujalski

* HORRENDOUS PICK *

An abysmal effort in attempting to bring meaning to style, Computer Chess goes no further than a tedious exercise in stretching (bad) ideas until they tear. The film’s major selling point is that it was filmed using ancient video cameras, documentary style, in order to capture the spirit of the wild frontier of technology in the late seventies. But spirit seems to be the farthest thing from the filmmakers’ minds in this case; instead, C-grade characters with B-grade potential are burdened with a D-minus concept. And we’re given the raw result.

An abysmal effort in attempting to bring meaning to style, Computer Chess goes no further than a tedious exercise in stretching (bad) ideas until they tear. The film’s major selling point is that it was filmed using ancient video cameras, documentary style, in order to capture the spirit of the wild frontier of technology in the late seventies. But spirit seems to be the farthest thing from the filmmakers’ minds in this case; instead, C-grade characters with B-grade potential are burdened with a D-minus concept. And we’re given the raw result.

Computer Chess is set at a grimy hotel in the middle of sunny nowhere, where professors and graduate students from all over the nation (world?) have convened to pit AI against AI on the fairest battlefield of them all: chess. The technology, however, is not the focus of the movie. It barely registers as a footnote. Instead, Bujalski is more interested in the interactions between the socially inept main characters; the “humor” of the movie is derived from basically two punchlines: “Haha, they’re nerds” or “Haha, it’s just chess.” If you can’t tell, this gets old after the first 8 minutes of the film.

Bujalski is most famous for making Funny Haha, often credited as the first true Mumblecore film, which happens to be my most hated recent cinematic movement. With Computer Chess, we are witness to exactly why Mumblecore can fail disastrously under the weight of its own pretense. Ostensibly, the freedom and lo-fi ethos of a film like Computer Chess would allow some sort of unexpected, organic humanity to shine through. But the film launches no such noble attempt; rather, it is self-satisfied from the get go, smug in its own concept and not concerned with making sense at all of the product.

While there are characters in the film to root for (the innocently naïve Peter and the sheepishly demure Shelly come to mind), it’s not enough to fight the ever-present urge to simply turn the film off. You can’t blame this on the cast, either; most of the cast are first-and-only-time actors, no doubt so the “rawness” can shine through. But there’s simply nothing to work with, no substance or subtext to interpret. This movie would be just as boring and insufferable if Daniel Day Lewis played every role.

Supporting Computer Chess and the people behind it would be akin to pampering a spoiled brat. You gotta sniff these out in the beginning, otherwise they’ll just repeat their awful mistakes over and over again.

*I typed in Computer Chess three times into Google but instead Freudian slipped into “coffee enema”, which would’ve been much more enjoyable to write about than this film.

A Hijacking — Kapringen (Denmark)

Directed by Tobias Lindholm

* TOP PICK *

A Hijacking is a Danish drama set primarily in two locations: aboard a small ship that has been hijacked by Somali pirates, and in an extremely sterile, white-walled office in Copenhagen. Though the film never stretches outside of these narrow confines, its human-centered drama is consistently compelling in its ability to show that any human being is capable of dynamism when placed in bizarre and challenging situations, whether he is a pirate or a money-hungry businessman. It’s a slow, tense psychological thriller, where communication between negotiating parties plays out slowly and unpredictably via phone and fax, over the course of more than 150 days. Most of these are bleak, though moments of interpersonal human communication and joy over simple life victories do lighten the mood on occasion. A Hiajcking ends with silent credits — no music; no flair; not even stylized color or text — and the weight of the film’s realism becomes ever-pronounced when the entire audience is left in silence, pondering not necessarily over the meaning of life, but on the variability of human nature in critical moments, the lack of predictability of fate and reaction. - Vivian Hua

May 31, 2013 – 1:30pm – AMC Pacific Place 11

The Forgotten Kingdom (United States, South Africa)

Directed by Andrew Mudge

Split equally between Johannesburg, South Africa, and Lesotho, a mountainous region land-locked on all sides by South Africa — The Forgotten Kingdom is a journey film about Atang, a young man who surprisingly discovers himself after the sudden death of his estranged father. And it soon becomes a tale of love, as he travels over wide expanses to seek out his childhood friend Dineo, after running away from her father’s request that he take her as a bride. Visually, The Forgotten Kingdom is impeccable, each shot an unfolding natural dream that makes one want to travel to Lesotho to see its beauty in person. The narrative, however, though enchanting when it becomes whimsical and dream-like, often also feels unbearably sentimental and cheesy, even complete with bad music. Characters and situations pop up along Atang’s journey that help him, often passively, come more fully into realizing himself through reminding him that he is the man he is because of his father. Many of the film’s ideas are fantastic at a macro level and on paper, but when executed, often come on too hastily, making the entire film seem rather fragmented as it transitions in and out of scenes seemingly with little rhyme or reason. In the end, the journey itself only feels important because of its end goal and result — hardly because of the journey itself. - Vivian Hua

Split equally between Johannesburg, South Africa, and Lesotho, a mountainous region land-locked on all sides by South Africa — The Forgotten Kingdom is a journey film about Atang, a young man who surprisingly discovers himself after the sudden death of his estranged father. And it soon becomes a tale of love, as he travels over wide expanses to seek out his childhood friend Dineo, after running away from her father’s request that he take her as a bride. Visually, The Forgotten Kingdom is impeccable, each shot an unfolding natural dream that makes one want to travel to Lesotho to see its beauty in person. The narrative, however, though enchanting when it becomes whimsical and dream-like, often also feels unbearably sentimental and cheesy, even complete with bad music. Characters and situations pop up along Atang’s journey that help him, often passively, come more fully into realizing himself through reminding him that he is the man he is because of his father. Many of the film’s ideas are fantastic at a macro level and on paper, but when executed, often come on too hastily, making the entire film seem rather fragmented as it transitions in and out of scenes seemingly with little rhyme or reason. In the end, the journey itself only feels important because of its end goal and result — hardly because of the journey itself. - Vivian Hua

June 5, 2013 – 9:00pm – SIFF Cinema Uptown

The Fruit Hunters

Directed by Yung Chang

Directed by Yung Chang

Remember that episode of the Simpsons where Homer goes to the candy convention and the dude with the weird accent keeps talking about the Gummy de Milo, and then Marge comes in and says, “Could you stop saying the word Gummy?” Well this film is like that, except replace accented-dude with Bill Pullman and “gummy” with “fruit”. - Allen Huang

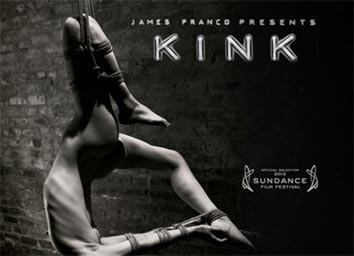

Kink (United States)

Directed by Christina Voros

Kink is definitely not the most well-crafted documentary — its interviews are often fairly scattered and become repetitive towards the end — but is definitely fascinating in its reveal of a not oft-considered subculture, as it offers explicit industry-specific sex scenes and dives into the reasons people become involved. In short: it’s not life-changing, but it is interesting. - Vivian Hua

More Than Honey (Germany)

Directed by Markus Imhoof

There has been wide speculation about the causes behind the global disappearance of bees, and More Than Honey attempts to explain the mystery through a series of interviews with people from around the world — specifically, in the United States, China, Switzerland, and Australia — who have intimate relationships with bees through farming, honey production, and biological study. Like most nature documentaries, there is a bit of a moral tale to be told, of mankind’s cruel treatment of the environment and of bees, in exchange for goods and money and so on; but there are also solutions presented, although they are admittedly bleak. More Than Honey is an informative documentary with some truly stunning and detailed shots of bees at work and in flight. - Vivian Hua

Moon Man – Mondmann (Germany)

Directed by Stephan Schesch

Directed by Stephan Schesch

* HORRENDOUS PICK *

Call me a hateful old man, but this film straight-up stinks. Moon Man looks like it was drawn by 400 drunk children in separate rooms, sounds like it was written by an alien caveman, and has the budget of your favorite elementary school drug abuse educational video. Any rambunctious charm the film attempts to conjure is instantly derailed by just how enthralled the film is with itself. - Allen Huang

Northwest – Nordvest (Denmark)

Directed by Michael Noer

* TOP PICK *

Michael Noer is a gritty realist, concerned with the unstoppable inertia of the city. Crossing back and forth between documentary and fiction, Noer sees no line between the constructed plots of his films and the real-life social fissures in Danish society. His depictions of the malfunctioning systems that entrap youth into a life of crime and poverty are starkly grounded in reality, which makes the characters in his films all the more believable and tragic.

Northwest is a perfect realization of Dogme-era filmmaking: gritty, natural, spontaneous — yet regulated, deliberate, purposeful. Each shot and each scene is a controlled strike to a vital point, every scene punctuated with heartbreaking efficacy. Northwest compares favorably to a film as essential as City of God, in that the two young co-stars are the lifeblood of this urban tragedy. This film captures the spirit of youth just as well as any other.

Real life brothers Gustav Dyekjær Giese and Oscar Dyekjær Giese play brothers Caspar and Andy. Caspar is on the cusp of manhood, and for him, that means accepting the mantle as a bonafide gangster youth. His crimes are petty and mundane at first (his stealing a PL Artichoke from a flat guarded only by an excitable little puppy brings the laughs), but eventually escalate out of control as ambition and hubris get the best of him. The downward spiral that consumes Caspar and his brother is deceptive in its mundanity, but none of this is skipped by Noer, since the deception is just as important as the actual crime.

This is a film that elicits “wow’s” and breathtaking moments. This is a film that doesn’t require breathtaking cinematography (unless you count that of the unkempt basement in a suburban brothel) to maintain your attention. This is a film that lays everything out, provides a simple narrative, and effortlessly evolves into a multi-layered, compelling coming of age film. This film is a must-watch. - ALLEN HUANG

Pieta –피에타 (South Korea)

Directed by Kim Ki-Duk

Like hanging out with an old friend, Pieta finds Kim Ki-Duk up to his same ol’, “I hate humanity” tricks. Upgrades are: digitally shot, handheld camera, surrealistic urban setting (literally everyone works in a dank mini-factory where they make only one thing), wonderfully insane mother-son montage in the middle. But in addition to being a sadistic exercise in revenge (see: Vengeance Trilogy), Pieta actually makes some interesting peripheral statements on the modernization of Korea and the increasing disenfranchisement of the middle-class. I can’t remember the last KKD movie with multiple points. - Allen Huang

The Fifth Season – La Cinquième Saison (Belgium)

Directed by Jessica Woodworth and Peter Brosens

As directors Peter Brosens and Jessica Hope Woodworth tell the story of a small village in Belgium that becomes stuck in a perpetual winter, they become get lost under the weight of a potentially good idea. There are some amazing cinematographic shots throughout the film, but they unfortunately aren’t enough to really keep up one’s interest, as the directing duo’s approach to the film is to let the pictures tell the story instead of the focusing on the story itself. As the town crumbles into mad terror, crops die and people starve, but it is hard to be sympathetic to anyone because the dialogue is so sparse; these are less human beings and more just moving figures. A few scenes appear, almost as art for the sake of art, and whatever metaphor was supposed to be hammered home becomes more an annoyance than anything as the film comes to a close. - Peter Woodburn

Our Children – À perdre la raison (Belgium)

Directed by Joachim Lafosse

At the start of Our Children, a young couple frolicks about, madly in love, over-the-top saccharine, full of wordless smiles and child-like naivete. Soon, an elderly doctor, clearly a father-figure in the young man’s life, appears. He warns the young man against a serious relationship with the young woman, citing the cultural difference of her being Belgian and him being a Moroccan immigrant as a prime reason. This disapproval offers the first signs of strain, hinting that the young man is somehow indebted to the older man, though the reasons are unclear.

At the start of Our Children, a young couple frolicks about, madly in love, over-the-top saccharine, full of wordless smiles and child-like naivete. Soon, an elderly doctor, clearly a father-figure in the young man’s life, appears. He warns the young man against a serious relationship with the young woman, citing the cultural difference of her being Belgian and him being a Moroccan immigrant as a prime reason. This disapproval offers the first signs of strain, hinting that the young man is somehow indebted to the older man, though the reasons are unclear.

Shortly thereafter, after a series of strange communicative moves between all parties, the young couple move in with the man, and, in yet another awkward bout of communication, reveal to him their plans for marriage. The older man voices pleasure though it is known to the audience he is rather dissatisfied; nonetheless, he offers to pay for the couple’s honeymoon because they can’t afford it. The couple naively invite him to join in on their honeymoon as thanks for his generosity, and he accepts, thus cementing a bizarre and inappropriate relationship triangle. Years pass and they all continue to live under one roof. One-by-one, four children enter their lives, adding pressure and taking up more of the already difficult-to-find space, as the three adults become more and more entangled and volatile in their treatment of one another.

In addition to the interpersonal element of the film, Our Children also seems to wish to offer cultural commentary on differences in culture-specific relationships to elders and to marriage. It moves back and forth from family-to-family and Morocco and Belgium in an attempt to drive home this point — but this idea, while very central to the narrative of the film, only seems to have minimal impact. Though the film is never boring and the main characters do a fine job or portraying a relationship’s shift from bliss into tragedy, there is ultimately something that leaves viewers wanting more. The extent to which the characters cannot communicate or help themselves is unrealistic, in way that is not even frustrating, but ultimately just devoid of emotionally-invested interest. Suspension of disbelief always feels just a bit out of reach. - Vivian Hua

May 31st, 2013 — 1:30pm — SIFF Cinema Uptown

Stuck in Love (United States)

Directed by Josh Boone

Directed by Josh Boone

* HORRENDOUS PICK *

Is there such thing as a director’s anti-touch? Greg Kinnear and Jennifer Connelly participate in a drudge of a film, which feels like it was written in 2001 and cribs awkwardly from films like Wonder Boys and Can’t Hardly Wait. Oh no! Coke! Oh no! A drinking problem! (She drank two glasses of champagne then did a line of coke.) References to Elliot Smith and Fevers and Mirrors and physical media abound. 2012 is confused. - Allen Huang

Two Weddings and a Funeral – 두 번의 결혼식과 한 번의 장례식 (South Korea)

Directed by Kim Jo Kwang-Soo

Directed by Kim Jo Kwang-Soo

I can’t tell if this movie is incredibly progressive or incredibly regressive. The gay caricatures are a step back. The handling of gay relationships (between non-caricature types) are actually pretty mature. There are some deft jokes that don’t resort to, “LOL, he’s gay” as the punchline. And the film works as both a character study and a, “We’re here; we’re queer,” statement to the socially-conservative Korean status quo. I guess, a net positive all around. - Allen Huang

The Wall – Die Wand (Austria)

Directed by Julian Roman Pölsler

* HORRENDOUS PICK *

The Wall centers primarily around one main character, a woman who wakes up one day to find that she cannot move beyond an invisible perimeter that extends outwards from her home. While there is the occasional fascinating detail — she can see a couple beyond the wall but can’t touch them and presumes them dead; she tracks how far she can travel from her home before nightfall — these rare moments are bogged down by far too much horrible amateur narration and kindergarten poetry, and the film’s use of a dynamic range of emotion is practically non-existent. Not at all recommended, unless you want something to complain about, for this is one of the worst films I have seen in a long time. It’s based on the novel by Marlen Haushofer, which I can only hope is far superior to this; but if in fact the words were taken verbatim from the novel, director Julian Roman Pölsler should definitely have chosen better source material. - Vivian Hua

The Wall centers primarily around one main character, a woman who wakes up one day to find that she cannot move beyond an invisible perimeter that extends outwards from her home. While there is the occasional fascinating detail — she can see a couple beyond the wall but can’t touch them and presumes them dead; she tracks how far she can travel from her home before nightfall — these rare moments are bogged down by far too much horrible amateur narration and kindergarten poetry, and the film’s use of a dynamic range of emotion is practically non-existent. Not at all recommended, unless you want something to complain about, for this is one of the worst films I have seen in a long time. It’s based on the novel by Marlen Haushofer, which I can only hope is far superior to this; but if in fact the words were taken verbatim from the novel, director Julian Roman Pölsler should definitely have chosen better source material. - Vivian Hua

Wolf Children – おおかみこどもの雨と雪 (Japan)

Directed by Mamoru Hosoda

Mamoru Hosoda’s quietest film is a tribute to strong mothers everywhere. Wolf Children is less about the fantasy of being a Halfling as much as it is the struggle of raising children through their awkward adolescences. Hana is the anchor of the film, the emotional focus and the sole multi-faceted character. Given the film’s pinpoint focus, the scope seems much smaller than that of Hosoda’s Summer Wars or The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, giving the impression that this is the least accomplished. But with all the off-beat comedic notes and the periods of ambient meditation that are Hosoda’s hallmarks, Wolf Children holds up to his other works. - Allen Huang

Mamoru Hosoda’s quietest film is a tribute to strong mothers everywhere. Wolf Children is less about the fantasy of being a Halfling as much as it is the struggle of raising children through their awkward adolescences. Hana is the anchor of the film, the emotional focus and the sole multi-faceted character. Given the film’s pinpoint focus, the scope seems much smaller than that of Hosoda’s Summer Wars or The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, giving the impression that this is the least accomplished. But with all the off-beat comedic notes and the periods of ambient meditation that are Hosoda’s hallmarks, Wolf Children holds up to his other works. - Allen Huang

Ω

Related posts:

- Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) 2013 Preview: Films We’re Looking At Potentially Being Excited About

- Portland International Festival 2013: Festival Preview & Picks

- Portland International Film Festival 2012: Documentary Film Preview Guide

music art film review - REDEFINE magazine

Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) 2013: Mid-Point Review of Best & Worst Films