![Alma - Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

In the directorial debut of their feature film,

Borrufa, Portland-based artist, performer, and filmmaker

Roland Dahwen presents a quiet portrait of the trials and tribulations faced by immigrant families in the United States.

Poetically and ambiguously named, Borrufa is shot on Super 16mm film stock and unconventional by most mainstream filmmaking standards. Drawing from a fifteen-page script as the basis for a two-hour, Spanish-language narrative, Dahwen intentionally creates a frame within which non-actors are empowered to co-create their characters, then encourages unscripted moments to blossom, allowing time and space for real-life experiences to unfold inside their loosely scripted narrative.

Borrufa is proof that Dahwen is an emerging filmmaker to watch. Their singular approach to craft showcases the understanding that some of the strongest filmmaking — while a synthesis of a creator’s imagination and insights — is very much in conversation with collaborators, and at the mercy of universal rhythms and whims.

VIDEO & TEXT INTERVIEW BY VIVIAN HUA 華婷婷; FILM REVIEW BY JACKIE MOFFITT

Video Interview w/ Borrufa Writer & Director Roland Dahwen

Thank you for making such a lovely film; it totally, immediately blew me away. I was not expecting what it was. To start off, can you tell me a little about the title, Borrufa, and how you came to choose it?

The title was a word that I learned years ago — a Catalan word, actually — and it means “snow that falls from a cloudless sky.” In the Pyrenees, when it snows on the French side, the mountain peaks will block the snow and the clouds, but the wind will carry the snowflakes over. “Borrufa” is to describe this phenomenon that happens, and it was really a word that I liked. I just put it as the title of the very first paragraph that I scribbled down, at least seven years ago, when I sort of began the slow writing of this project. And it was not the confirmed title until the very end, when we were doing the credits, and it was still just the working title.

In some ways, for lack of finding a better title, we left it at that.

But I think that there’s a connection with the sort of idea of the unexpected things that life brings us, and I guess, also, I wanted a title that was sort of abstract to a lot of people — maybe a lot of people wouldn’t have a lot of associations with the word. I was interested in having a title like that, that didn’t say too much, I guess.

You said you started writing it seven years ago, and I saw that it was sort of co-written with other writers, also. Can you just tell me a bit about the process of writing this script?

Yeah, it was based on a true story, in the sense — as much as any stories are true, I guess — and it was sort of just the vague plot points about a family who — the father has a second family, who he kept in secret for a long time, and then he discovers this sort of — the second family, the daughter he had with this other woman, wasn’t his.

That sort of sat for a long time, and I would sketch out different scenes — and then it was… I really stopped writing it for a while until I found the actors to play the parts. And then that restarted the process of writing, and I very much wrote the characters with the actors in mind — so knowing their habits; knowing how they spoke. Details of their lives. And they, in many ways, are co-creators of all the scenes, because so many of the scenes were their suggestions. Were things that come from their lives — routines, habits. We incorporated all of those.

The script was very vague, in a lot of ways. It was maybe fifteen pages or something? And it was really just describing these scenes, describing these circumstances, these situations, in which the characters found themselves. And then, I would write some dialogue, and I would record myself saying it, and I would send it to the actors, or we would do it in person. So the actors never saw the full script ever. Then they would sort of learn it through the recordings or through our rehearsal, but they would also add to it and change things and ask me questions, and create moments and create dialogue that is much better than anything I could have written.

It was sort of a long process of writing it, and very much with the actors, who were fantastic, and added many, many elements to all the scenes, that I didn’t anticipate.

That is extremely fascinating to me that the script was fifteen pages, because you did — if I’m not mistaken, have a fair bit of grant funding to fund this? Is that correct?

Yeah, we had two main — there was a fellowship and a project grant, basically — and I wouldn’t say it was a lot of money by any sort of film standards, but it was a little bit. I think part of it was that I applied for funding saying it would be a shorter film. So, in many ways, I sort of slipped it in there, because — from most people’s outside perspective, it was maybe difficult to imagine that somebody who hadn’t made a film before wanted to make a long film on Super-16, having not had experience in the industry, really, so pitching it as a short film allowed me to begin the process of financing it.

Kudos to you — because that was exactly where my line of questioning was going. People who would be looking at it would be like: a fifteen page script? That can’t possibly be a feature — and really good on you to hack the system, knowing that.

Pfft, yeah, it all comes… you pay now, or you pay later. I think I was very fortunate, and a lot of people supported it, and it was — like many, many projects, it was made possible by people’s time and energy and donations and giving to it, in many, many ways. It’s owed entirely to everybody… everybody who worked on it.

![Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

Borrufa Feature Film Review

BY JACKIE MOFFITT

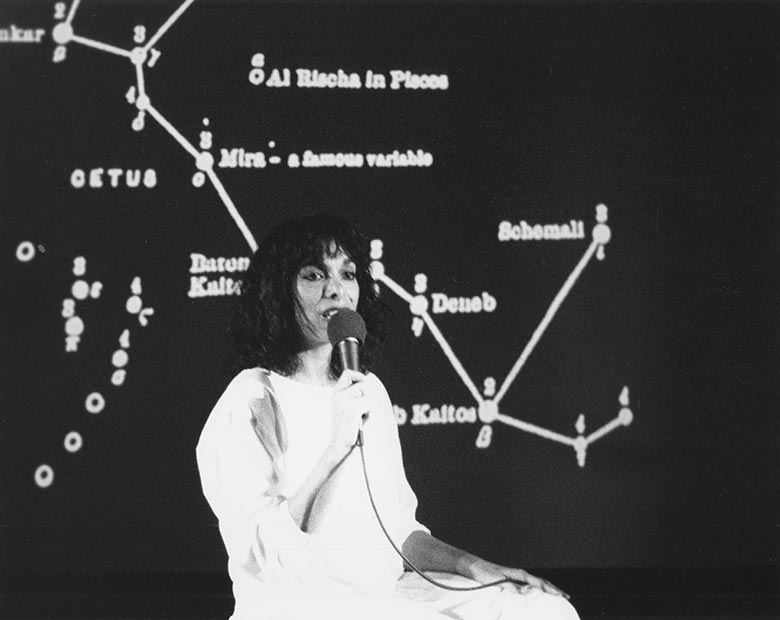

Borrufa explores the quiet tensions that emerge when Ireneo, the father of an immigrant family living in Portland, is revealed to have a second family and the mother, Leonora, considers leaving him.

The film takes a very slow, contemplative pace, drawing attention to the small rituals of day-to-day life, while emphasizing both the bonds and the growing distance between the family members. Leonora regards her adult son Heldáy with a deep sense of tenderness and devotion as she weighs leaving the family. The sense of care between the characters is also showcased in a scene where Leonora poignantly washes her mother’s feet, showing their naturalistic and gentle rapport. The grandmother is clearly in her last days of life and reminisces about her childhood home.

A sense of melancholy and loss pervades the film, with the son Heldáy falling unexpectedly ill. Leonora sings him a lullaby in another tender scene. The next day, we see him sitting at a table feverishly sketching a portrait, showing a window into his inner life.

The father, Ireneo, stubbornly holds onto his desire for the family to stay together, which his family seems to want no part of. Ireneo has a penchant for long philosophical monologues in the company of his often disinterested son. In one scene, Heldáy stands on a ridge with Ireneo, who discusses his frustration that his mother underestimated his intellectual capabilities growing up. Heldáy stands by silently throughout his father’s speech, unable to respond, with his hands in his pockets and his head down.

When Ireneo and Leonora at last confront each other about the infidelity, Ireneo attempts to prompt Leonora on what to say, using conciliatory terms that she does not accept. The cinematography is still and austere, drawing attention to the introspection and loneliness of the characters. The audio is minimal, without any use of non-diegetic music, which further enhances the film’s atmosphere of repressed conflicts. The understated visual style conveys a sense of weighty isolation.

Borrufa shows a family whose relationships are rapidly fraying, and yet no one ever raises their voice. The long silences form a language of personal catastrophe. In only a few scenes do we get the sense of a wider world than the nuclear family. One is when Lenora is with her sisters, who were kind and supportive as Leonora discusses her son and the prospect of leaving Ireneo behind.

![Opening Scene - Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

This line of questioning will probably extent throughout the whole film, but starting with the introductory scene: it was a super great way of setting the pace of the film, I feel like — showing how long the shots are; how little action can happen yet convey a really strong emotional weight… and I was wondering, specifically, how that scene came to be.

I think it came from a lot of different places. One of them is: there’s something very, very special about getting your hair cut. There’s a very intimate moment. When I was a kid, I used to fall asleep at the barber shop all the time. I found it so relaxing to get my hair cut, and I think there is a lot of emotion that is tied in with cutting hair and how people have their hair.

I was interested in this moment of: there is this moment in which the husband and wife — it’s something they’ve done many times before — where she goes outside, and she cuts his hair out in the driveway in front of their house, and I wanted to show the sort of… routine moment that they have. It’s a habit they’ve built up over years, but that’s all of a sudden intensified by what’s going on. And in this moment, maybe it’s not completely clear if — who knows what about the drama. Does the wife know? Does she suspect? You don’t know, and it’s sort of ambiguous, like much of the film. And the husband also doesn’t know what she knows. He maybe suspects, you know.

So I wanted to set this up, and it was a way of introducing their relationship, and sort of implying their past history in this moment. And then you get to see, you get to learn about the character of the father, Ireneo, through his posture and how he carries himself, and how he waits. I think part of it is thinking about how we as people — how we look when we’re waiting for something, is I think, perhaps indicative of our state of mind or our state of being. I think we learn something about him, even in these moments where he isn’t saying anything. How he sets up the towel, and how he sort of sits up again when he knows that she’s about to come outside, and then how he responds when she almost immediately starts cutting his hair and stops cutting his hair. Those are some of the motivations, I think, that I was thinking about and wanted to explore in that first scene.

Love it… when watching the film — it feels like probably the way you direct actors is very specific to you, and I want to explore that a bit, because in watching it, it’s like: how do you know when a shot has reached its full potentiality? Is that through a cue that you’re giving to the actors directly, or is that through an internalized cue that they have or some other mechanism?

Yeah, I mean, this is a part of the process that I absolutely love. Working with people, and trusting them in many ways, and sort of setting up these situations and — I’m very thankful to the actors, because they… I put them in demanding situations, in many ways. They’re long takes. If anybody, if you’ve ever acted — long takes are very hard on people. They’re very exhausting, and there isn’t; there was no coverage. There was no cross-cutting between different angles, and oh, we do this take, ten, twenty times. There were no close-ups… all of these mechanisms people use to hide things. All that was gone. There was no music to sort of amp up the moment. The actors were very patient with me, and wonderful, and were very concentrated in each scene.

One of the techniques we used was: we didn’t slate anything at the beginning. I would sort of touch or give a sign to the Director of Photography [Edward Pack Davee], and he would begin, and we would signal with the sound recordist, and they would begin recording. But it was all very quiet, and we would slip into the moment, and people weren’t exactly aware of when exactly we were beginning to film or not.

We didn’t have this moment of the clapper sounds, and everyone tenses up, and we have to act, all of a sudden. I would tell all the actors to get ready, and they would begin, oftentimes, and we would all sort of slip into the filming. Sometimes I would let the scene continue even beyond anything that was written or and cues we had or any actions we had planned. Sometimes to see what the actors would do, because there’s these moments — there’s these very intense moments of when we don’t have a plan. What do we do with ourselves? Which I feel like is very true to life, you know? So oftentimes, I would let the scenes continue, and then we would tail slate it at the very end… but I think part of it is — I’m sure we’ll address this, but I think it takes a long time to understand anything. And these are long moments, and they all could be longer, in my mind, a little bit.

I don’t know if that answers your question, but yeah.

It does. For each scene, would you do multiple takes? Or was it one and done, often?

The most takes we did were three takes for one scene. Most of them were one or two. And part of that was a financial restriction of not having the resources to do more takes. But early on, I knew I didn’t want to be doing multiple takes for everything. We definitely prepared in a very rigorous ways for all of the moments, and the production team and actors would very much concentrate in the moment and usually, we did it in the first one. Occasionally, there would be moments where in the first take, I knew I wouldn’t use that take, but I would still let it go… partially to show faith in the actors. I think there’s something when people are yelling “cut!” all the time with all these false takes and false starts that can erode people’s assurance in themselves as actors. So sometimes, I would let it go, even when I would know we wouldn’t use that take.

But the most we did was two takes, and one time, for just a technical reason, we did a third take for a scene.

I imagine — correct me if I’m wrong — but I’m imagining that most people who worked on your set have not worked on a set like this. Or have they?

I don’t think so… I was very careful about who I asked to be a part of this, because I was very conscientious of the sort of mood and energy on set. I think that different energy can be inappropriate sometimes for the scene that we’re trying to make. Some people had a lot of film experience and have directed their own films and are very much in this world as professionals, and some people had never been a part of it at all, but had certain skills or had certain personalities that lend a lot to the overall environment. And that was something that was important to me: not just, oh, we have to do whatever it takes to get these results.

It was important to me that people enjoyed the process in some way, including the actors. It was important that there was a lot of respect, I guess, throughout the whole making of it.

But yeah, I think it was hard on people. Especially the people who had sort of a lot more industry production habits. They were surprised when we said: we don’t have a wardrobe, really. There’s no art department. There’s no makeup. Like I said, we tail slated everything. I think they were surprised.

The first day — the first scene, when we just did one take, and it was an entire roll of the film, and that was good, you know? They were like: oh my god. How long do we have to be quiet for this take, you know?

I’m very appreciative to everyone for really putting so much time and thought into the making of this.

How long was your entire shoot for the film?

We did the first three days, and then a month later, we did the second three days, so it was only six days.

![Alma - Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

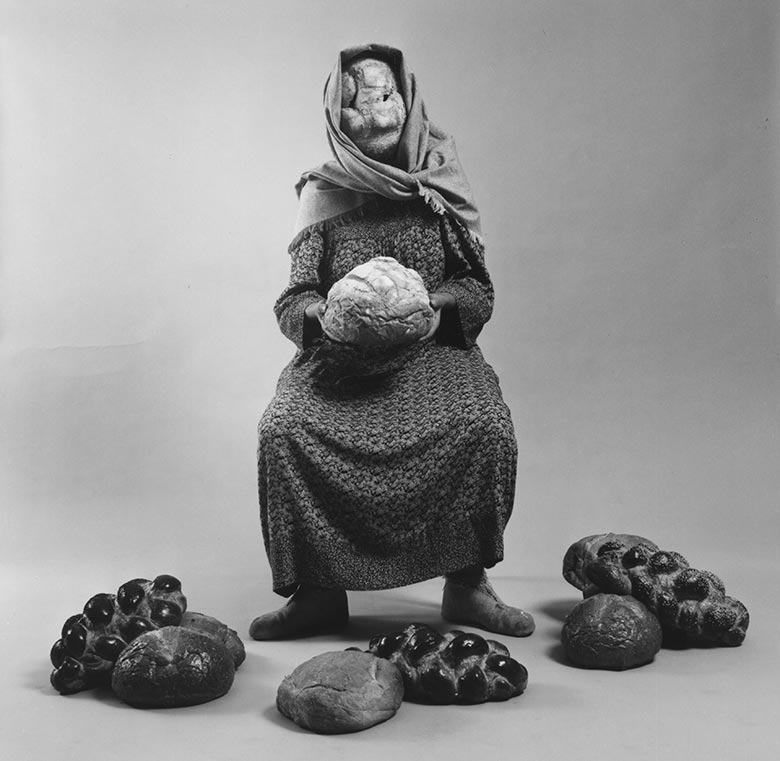

Can you tell me about the process of finding the non-actors to act?

Yeah. Like I said, I had written the script up to a certain point, and it was sort of vague and really a bunch of descriptions of scenes. It was maybe a couple years of just having it on pause and meeting people and thinking about people who I knew and wondering who might be willing and suitable and enthused by certain characters, you know? And then it all came together rather quickly in some ways.

I met the three main actors in very different contexts. One was Heldáy de la Cruz, who plays the character of the son… he was on the set of a music video that I was working on, and I just remembered something about him. Something about his presence and his certain type of — how he looked at things.

I slowly became friends with him, and he agreed to do it… quite reluctantly, I think. I think that’s something they all had in common. There was certainly some reluctance.

Alma [García], who plays the mother, is the mother of a friend of mine, and she was wonderful and really added so, so much to the film.

Antonio [Luna], who plays the father… I was helping out on a video project that was basically raising money for undocumented and DACA students at Portland Community College. They were raising scholarship funds for them, and they were making these videos with the parents of those students. And Antonio was the only father who agreed to participate in the interviews. The rest were all mothers. While I was filming that interview, I began thinking about the character of the father, because he had something about how he was able to articulate his own faults, which I feel like is maybe not so common, especially among male-identifying people. And he had both this sort of… pride, and this sort of ability to recognize things… maybe mistakes that he’d made… so all three of them, I met them in very different situations, and could not have done it without them, and they very much determined the contour of the film and the content of the film.

Did you rehearse with them a lot?

Yeah. Yes. I would go and sort of hang out with them. We didn’t do really formal rehearsals. We never filmed them… there were no acting coaches or anything, but a lot of it was just explaining — going through the details of each scene and each character.

We rehearsed it to varying degrees with people, because Antonio lives a few hours away and so, it was less easy to just go and see him. I’ve probably spent the most time with Alma. We would just go hang out and eat and have lunch and talk about things. So it’s rather informal in some ways, but it was sort of… it was a long build-up process. Oftentimes, on the filming days, we would spend some time in rehearsal, as is common, before we filmed.

But each time — oftentimes, the actors would say things that we hadn’t talked about in rehearsals, and I very much wanted that. I very much wanted a space for that. And so, as I’ve talked about before, we’d let the film, let the scene roll beyond what we had rehearsed, and Alma, especially, would add things that I didn’t expect. Sometimes those were really beautiful moments that she came up with entirely on her own.

![Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

![Alma and her mother - Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

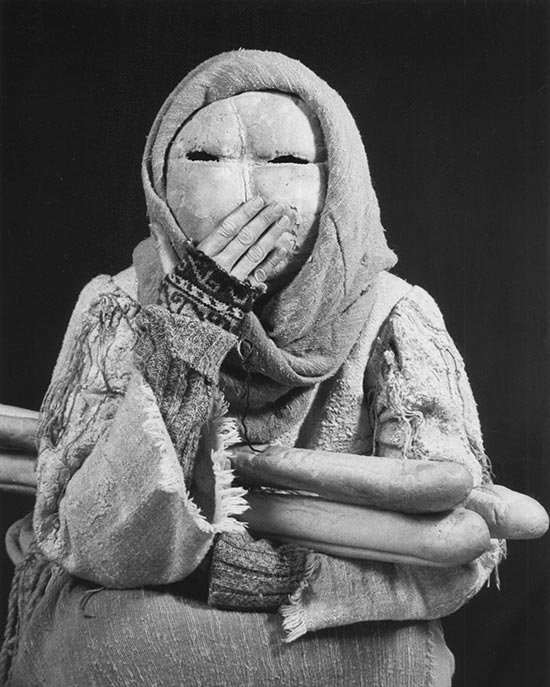

Do you have any favorite moments — or maybe one favorite moment that stands out to you in the film?

I mean, I don’t know how to answer that, really, but I would say that the scenes with Leonora, who is the mother, played by Alma, and her mom, the grandmother… they’re maybe the most poignant to me, because that’s Alma’s real mom in real life, and she passed away in December, a few months after we finished filming. So those are maybe… difficult to watch? Scenes that are difficult to watch, but maybe the ones that make me feel the most appreciative of Alma and her family for participating in the film.

There was one line that really stood out to me. There were many lines, but there was one where the dad is talking to the son, and his friend kind of says, very sad, that “the rain falls out of tune.” And that line just really stuck with me, especially with the son’s response and how they just completely are on different wavelengths. I guess, where did that story come from? Or is that from your imagination?

It’s a combination of things. That’s actually sort of a monologue that I had written early on. A version of it, early on… my father’s a musician, so bits of it come from things that he’s talked about around perfect pitch and around people who he knows who have had perfect pitch, to whom mechanical sounds will bother them. Those certainly informed early versions of it.

The line, specifically, I don’t know when I wrote it, but it was certainly something that was a piece that I had laying around. I think that there’s these moments of — the father’s monologue is where he’s sort of talking a lot, and he’s seeking solace in these ideas, and he’s also, perhaps, in the middle of his delusions in these moments. I think these really show something that I see all the time. People talk, either to avoid talking about something else… people try so hard to talk to each other in so many different ways, and in the end, usually we can’t. Usually we’re not able to communicate very well, and I don’t know. I don’t know how much I have to say about that.

No, that’s plenty.

Thank you for noticing that, yeah.

You know, it seems like you’ve done a fair amount of documentary work around immigration and maybe these populations of similar people, and now weaving it into a narrative is a really interesting way of showing it on-screen, and I’m wondering: is there anything that you want people to take away from the film?

Hmm. I guess to quickly talk about this idea of immigration… it’s something that’s important to me, certainly, and it is very present to me in the film, even though much of it goes unsaid. There’s no overt mention of immigration status or migration stories or immigration stories or country of origin. All that is very much left unsaid, but to me, is still very present. There’s a little hint of it at the beginning when the character — the son, Heldáy — they’re at the clinic. He’s at the clinic with his father, and his father says, “Oh, this is my son, Ángel.”

That’s basically a reference to Heldáy sort of having a public name, which is something that people who I know have done. Of having a public name, if they’re undocumented, to sort of protect themselves. Most people would maybe skip over that or just assume that he had two different names or something like that, but I was interested in making a film where we sort of take for granted that there is immigration… that there is immigration in Portland and in Oregon, and that people have rights to be where they would like to be, and I guess I wanted to have that sort of foundation that was unspoken, because I didn’t need to say it. This is assumed, and so, beyond that, what sort of explorations of persons of dignity can we talk about or look at? Beyond simply how people — what their relationship with the state is, what their political identity is.

And that’s very important, also. I’m not trying to disregard that at all, but I wanted to shift or maybe add a layer to things.

In terms of a larger takeaway for the film or something that I hope people will get from it: I don’t know. To me, it’s a film maybe about loneliness in a lot of ways… I think is how we, despite being among family, among people who we care about or who care about us, we end up being very lonely, still, and in need of a lot of solace. And so, that — I don’t know if it’s a takeaway, but it’s one of the sort of underlying elements of the film. We could all use some help, as they say.

![Ireneo at the Clinic - Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

That’s definitely true. Especially right now. I think the scene in the hospital, clinic… is so understated and so important because, without it, I think the film could be set in any sort of Spanish-speaking country but that slight scene just really set us in: oh, this is the U.S., and you have populations living this life that people sometimes don’t see.

Yeah. It was also curious because Heldáy, the actor, has worked as a medical interpreter before, and Antonio has… grown children. I remember when we were filming it, he was like, “Ah, feels very, very natural in a lot of ways, because we’ve done this before.” And Mary Lou, who you almost don’t see, but who plays the nurse practitioner, also has a medical background…

That was, I think, the last scene that we filmed, but I’m very happy with how it turned out. It’s interesting, because it was maybe the last scene that we filmed, but it was maybe the earliest scene that I wrote, way back.

It’s a really powerful scene. Even in the way that Mary Lou responds: her inherent understanding of Spanish, in some degree, I thought was super accurate and awesome. So kudos.

Thank you for noticing that.

I guess I have one last question, which is this quote that you told Portland Monthly, which is, “To me, the more heartbreaking moments are the ones in which people are doing their daily lives while something very tumultuous is happening inside of them.” I guess, in the context of right now, that is everyone… so much tumult both internally and externally, but we still have to do our normal lives-ish, as though the world were not falling apart. I’m wondering what’s coming to mind for you as a storyteller in this time? Things that you’re interested in exploring, or things that have come up in your mind?

Hmm… I don’t quite know how to answer this. I guess I would reiterate that the dramas that are inside of us are always there and probably aren’t going anywhere.

I don’t really know how to answer that with sort of a current time… yeah, I don’t know. I guess. I don’t know how to answer that, actually. I’ll keep thinking about that.

Are there any projects you’re hoping to work on next?

Yeah, there’s a few things. I’m getting to organize a film series with a few films, this fall, coming up, through the Cooley Gallery at Reed [College]. I’m organizing a couple film screenings of films that I like, and working on some things for myself, but maybe right now is not the right time to talk about them.

Fair enough. Cool, is there anything else related to Borrufa that you want to share?

No, thank you for your questions. Thank you for your detailed watching.

No, there’s so much to unpack in the film. Great job.

Thank you.

Borrufa Film Trailer

Original format: Super 16mm, color.

Running time: 109 minutes.

Screening format: DCP. 5.1 Surround sound.

2019. A Patuá Films Production.

![Alma - Borrufa Film by Roland Dahwen]()

About Roland Dahwen

Roland Dahwen is a filmmaker whose work explores migration, race, and memory. His video installations have shown in festivals, galleries and museums in the United States, Brazil, Cuba, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands. He is a recipient of the Oregon Media Arts Fellowship and an artist-in-residence in Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s Creative Exchange Lab. ‘Borrufa’ is his first feature film.

Ω

Some of the biggest music festivals around the world are emphasizing a "green" environmental focus, and now a few music festivals in China are encompassing a related focus.

Some of the biggest music festivals around the world are emphasizing a "green" environmental focus, and now a few music festivals in China are encompassing a related focus.

Photography by 2015 Tuborg GreenFest Music Festival

Photography by 2015 Tuborg GreenFest Music Festival

Photography by Hugh Bohane - (TOP) Slingshot recycling games; (BOTTOM) Helen Feng from Nova Heart.

Photography by Hugh Bohane - (TOP) Slingshot recycling games; (BOTTOM) Helen Feng from Nova Heart. By nature, music festivals are not the most environmentally-friendly affairs, and their carbon footprints are large, especially when huge generators are used. Promoters of Chinese festivals face many other difficulties as well -- the largest of which are costs and permissions.

By nature, music festivals are not the most environmentally-friendly affairs, and their carbon footprints are large, especially when huge generators are used. Promoters of Chinese festivals face many other difficulties as well -- the largest of which are costs and permissions.

When Bonobo included Khruangbin’s “A Calf Born In Winter” on his 2013 Late Night Tales mix, he placed the strumming, shuffling, soulful instrumental between some late night ambient classical piano and his own “Get Thy Bearings”, a silken smooth soul jam with UK chanteuse Szjerdene. Somehow, it all made sense, a block of music that delighted in a similar mellow, spacious gorgeousness.

When Bonobo included Khruangbin’s “A Calf Born In Winter” on his 2013 Late Night Tales mix, he placed the strumming, shuffling, soulful instrumental between some late night ambient classical piano and his own “Get Thy Bearings”, a silken smooth soul jam with UK chanteuse Szjerdene. Somehow, it all made sense, a block of music that delighted in a similar mellow, spacious gorgeousness.

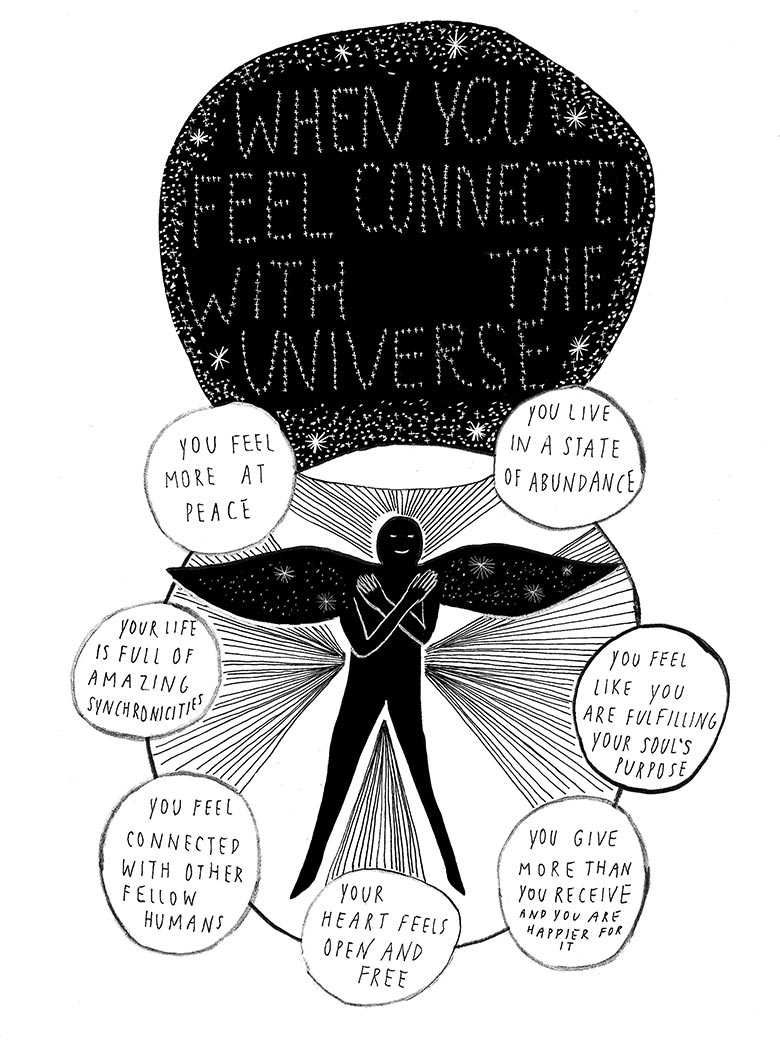

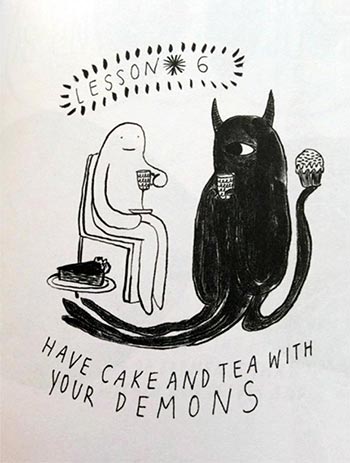

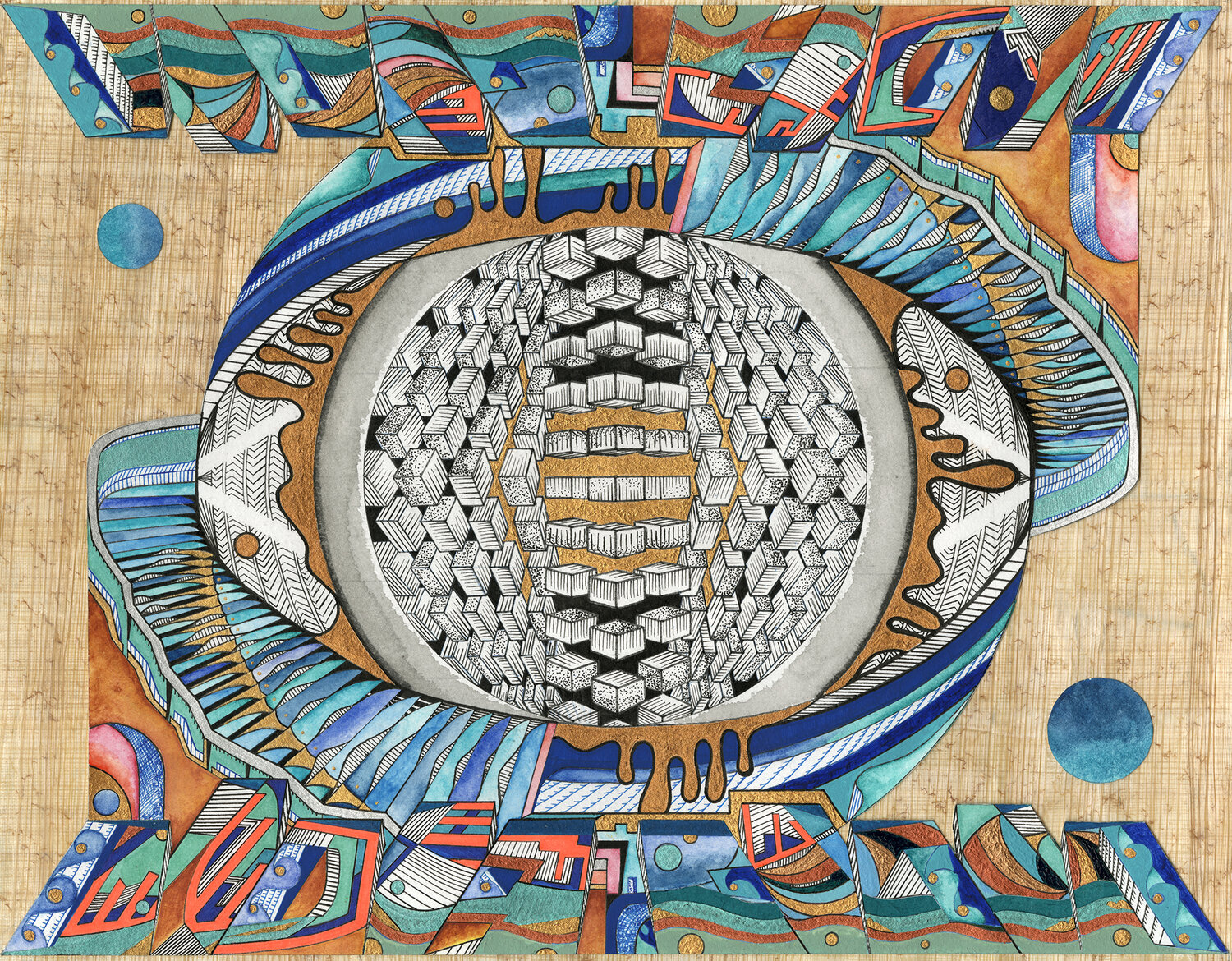

From Your Illustrated Guide To Becoming One With The Universe, 2014

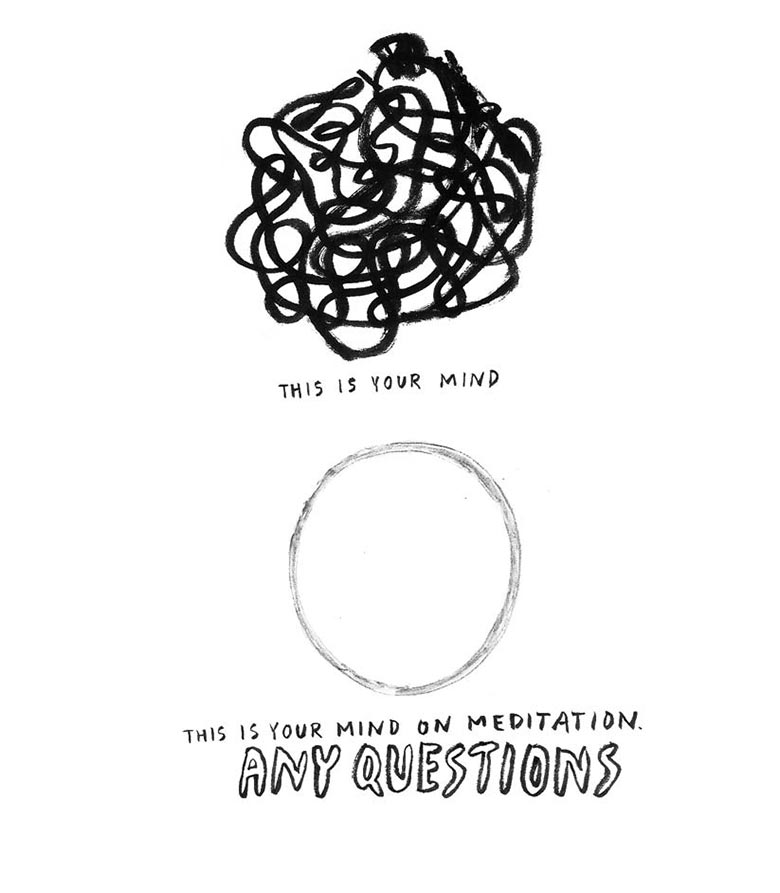

From Your Illustrated Guide To Becoming One With The Universe, 2014 Though Sakugawa’s comics can easily be broken down into basic building blocks, they have a sincere complexity to them. Her latest book, There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, is particularly focused on meditation, and utilizes tasteful watercolors to offer advice on everyday banalities, such as getting rid of bad moods, or larger-view goals, such as making intentions come true. Sakugawa details these lessons with epic statements that stir up deeply cosmic emotions as well as through the use of outlandish humor — but all ideas are connected by simple visual frameworks.

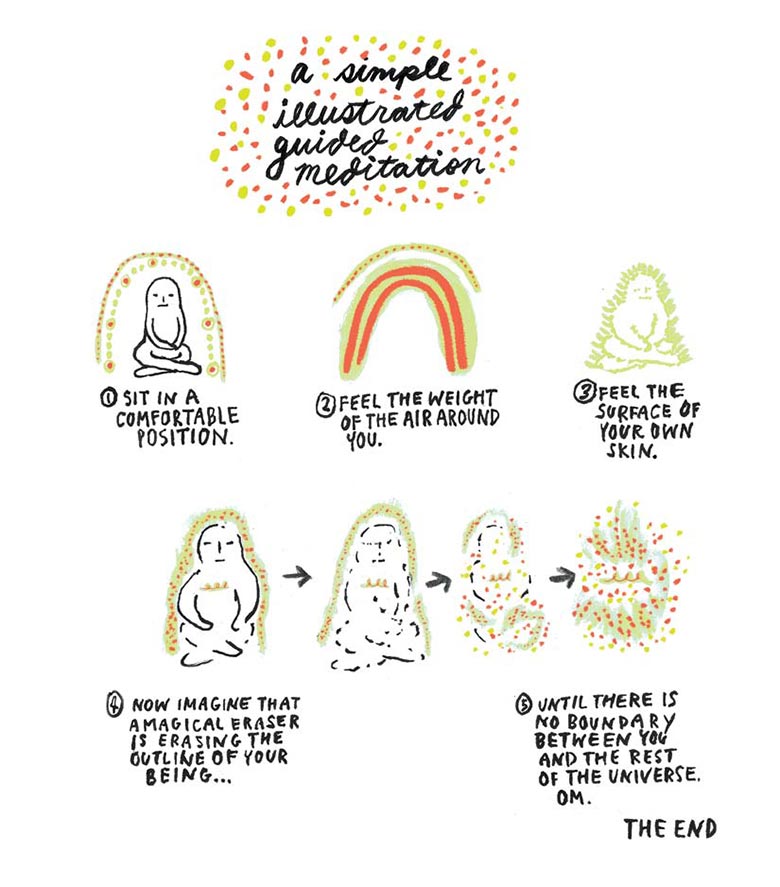

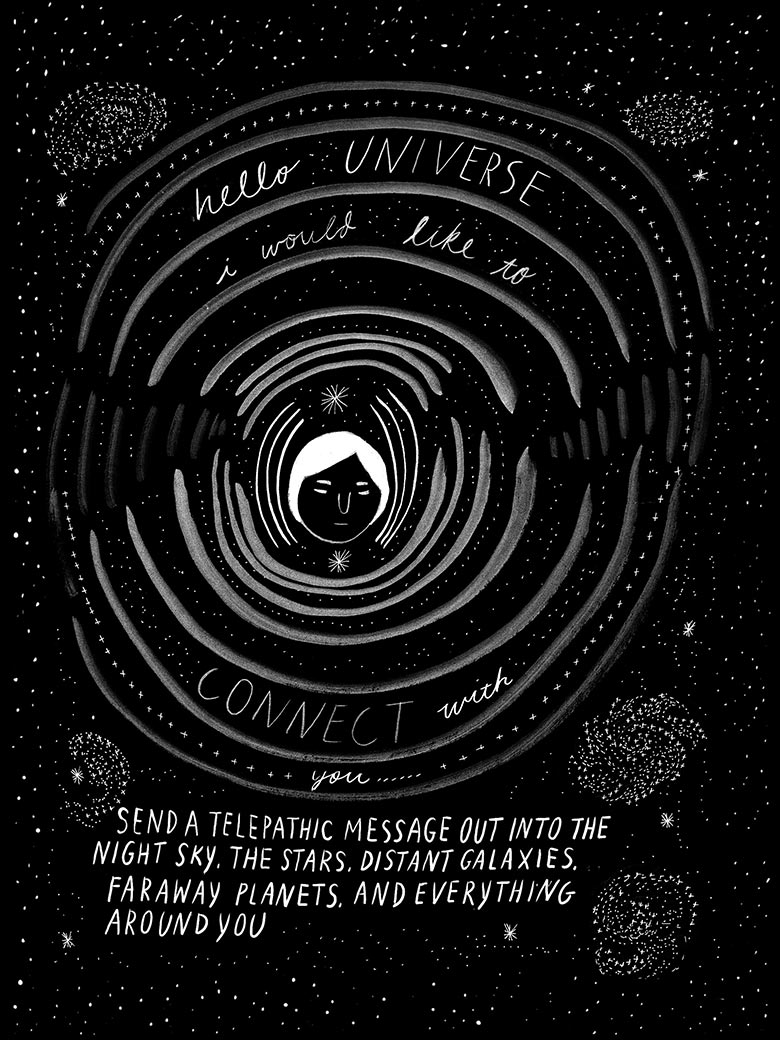

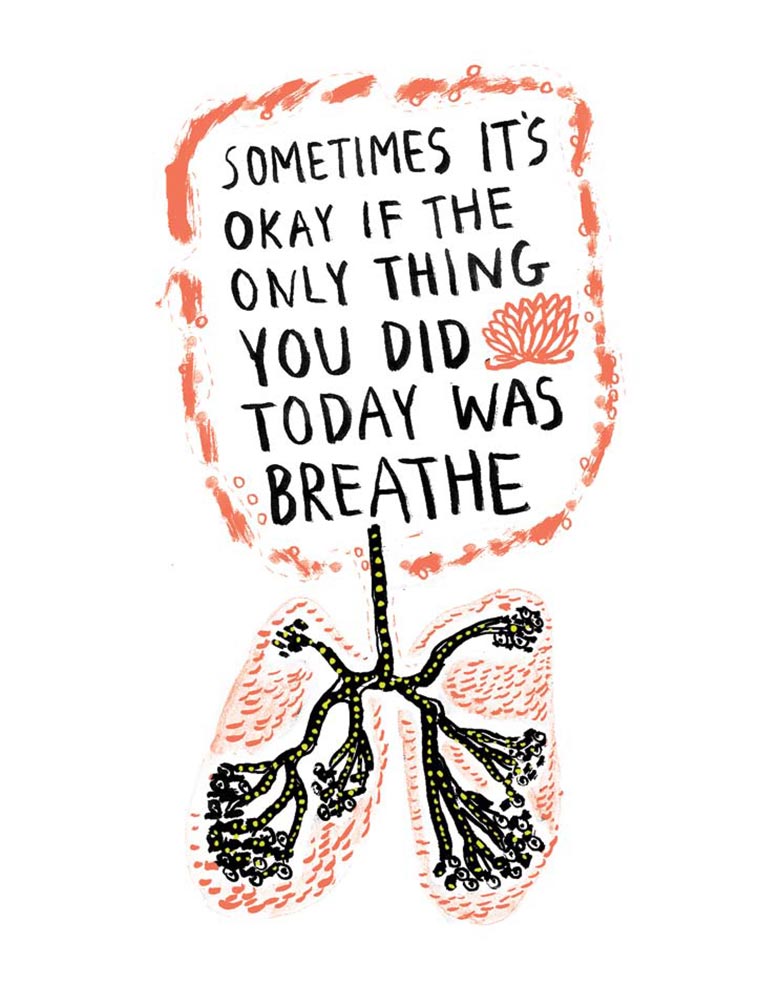

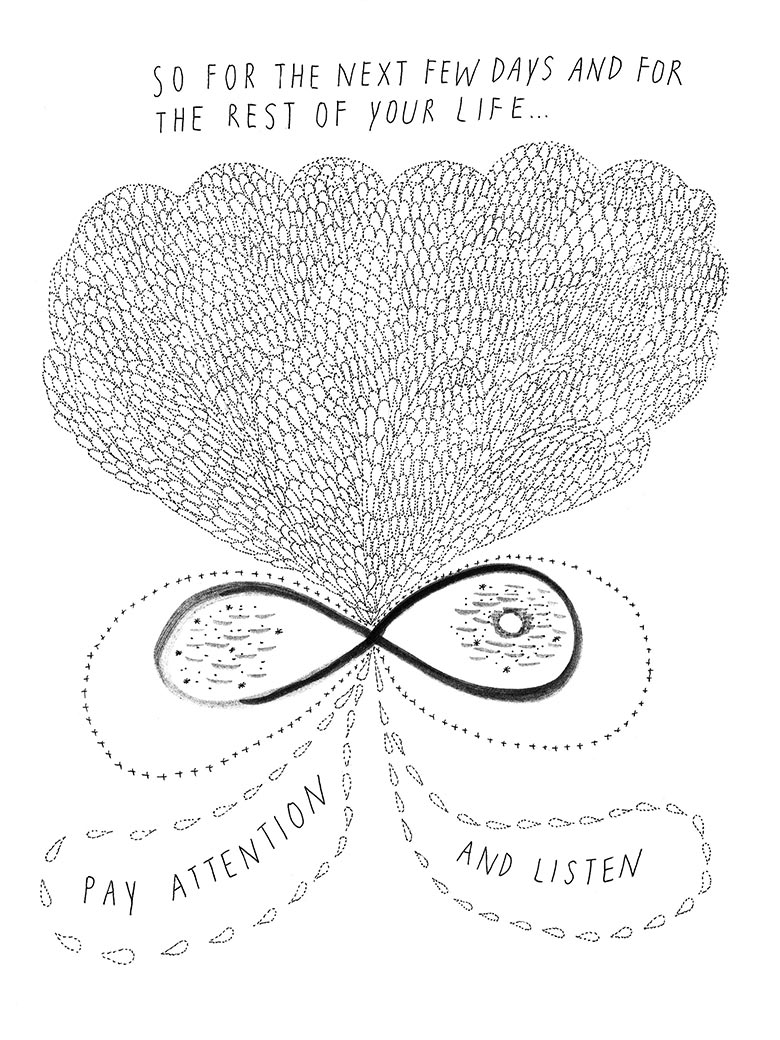

Though Sakugawa’s comics can easily be broken down into basic building blocks, they have a sincere complexity to them. Her latest book, There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, is particularly focused on meditation, and utilizes tasteful watercolors to offer advice on everyday banalities, such as getting rid of bad moods, or larger-view goals, such as making intentions come true. Sakugawa details these lessons with epic statements that stir up deeply cosmic emotions as well as through the use of outlandish humor — but all ideas are connected by simple visual frameworks. From There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, 2015

From There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, 2015 From There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, 2015

From There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, 2015

“[It] is always funny to me — not funny, but always a bit of a surprise to me, because I feel like a lot of the meditation and self-help work that I do, they’re primarily reminders to myself, not so much to other people, so it’s always a pleasant surprise that it helps people,” she shares humbly. “It just never gets old to me that people really respond to my work. It’s surprising every single time.”

“[It] is always funny to me — not funny, but always a bit of a surprise to me, because I feel like a lot of the meditation and self-help work that I do, they’re primarily reminders to myself, not so much to other people, so it’s always a pleasant surprise that it helps people,” she shares humbly. “It just never gets old to me that people really respond to my work. It’s surprising every single time.”

“So long as you’re financially sustainable, you’re really happy with the work you’re doing, and you’re still in the game, that’s great,” she states. “I wouldn’t say I’m poor, but I’m definitely not rich, and I’m nowhere close to buying a house like some of my peers. But I’m also really happy with my life and the freedom living this life brings, and even though it’s unstable and I have no idea what lies in the future for me, I’m really enjoying what I’ve built for myself, so I feel like that’s successful.”

“So long as you’re financially sustainable, you’re really happy with the work you’re doing, and you’re still in the game, that’s great,” she states. “I wouldn’t say I’m poor, but I’m definitely not rich, and I’m nowhere close to buying a house like some of my peers. But I’m also really happy with my life and the freedom living this life brings, and even though it’s unstable and I have no idea what lies in the future for me, I’m really enjoying what I’ve built for myself, so I feel like that’s successful.”

Photography by Susan Einstein

Photography by Susan Einstein

North Pacific Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, green abalone shell, brass, rope, shackle

North Pacific Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, green abalone shell, brass, rope, shackle

The “explorers” part of the equation is an important component. For one of their recent collections, Gyrecraft, Groves and Murakami partnered with a research vessel which set sail through the North Atlantic Gyre, a thing I did not know existed until I came across their work. It — along with the swirling mass of debris that collects there, known as the “North Atlantic Garbage Patch” — has been the subject of a good deal of research since the late 70s, when scientists first discovered it and an analogous patch in the Pacific.

The “explorers” part of the equation is an important component. For one of their recent collections, Gyrecraft, Groves and Murakami partnered with a research vessel which set sail through the North Atlantic Gyre, a thing I did not know existed until I came across their work. It — along with the swirling mass of debris that collects there, known as the “North Atlantic Garbage Patch” — has been the subject of a good deal of research since the late 70s, when scientists first discovered it and an analogous patch in the Pacific.

Indian Ocean Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, mother of pearl, aluminium, steel, brass, rope

Indian Ocean Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, mother of pearl, aluminium, steel, brass, rope South Atlantic Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, gold plated steel, brass, rope, sandblasted glass

South Atlantic Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, gold plated steel, brass, rope, sandblasted glass South Pacific Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, reclaimed hardwood, gold plated steel, brass, rope

South Pacific Gyre, 2015 – Sea plastic, reclaimed hardwood, gold plated steel, brass, rope

Dune Table, 2015

Dune Table, 2015 Hair Highway, 2014

Hair Highway, 2014 Meteorite Shoes, 2014

Meteorite Shoes, 2014

A Polish black comedy about a groom’s possession by a 17th century Jewish spirit, Demon never takes itself too seriously yet has moments of psychological unhinging which are plausible enough to be chilling. The film’s twists and turns never go into quite the direction you’d expect, and part of that is due to its multicultural nature and the fact that Polish weddings seem festive to next-level proportions.

A Polish black comedy about a groom’s possession by a 17th century Jewish spirit, Demon never takes itself too seriously yet has moments of psychological unhinging which are plausible enough to be chilling. The film’s twists and turns never go into quite the direction you’d expect, and part of that is due to its multicultural nature and the fact that Polish weddings seem festive to next-level proportions. This surreal sci-fi film is set on a remote island and filled with guardian “mothers” and young boys who are subjected to a number of mysterious medical tests. Director Lucile Hadžihalilović is married to Gaspar Noé, if that offers any insight into the type of unsettling feeling that Evolution might generate in your guts.

This surreal sci-fi film is set on a remote island and filled with guardian “mothers” and young boys who are subjected to a number of mysterious medical tests. Director Lucile Hadžihalilović is married to Gaspar Noé, if that offers any insight into the type of unsettling feeling that Evolution might generate in your guts. Werner Herzog talking about the internet. That is all.

Werner Herzog talking about the internet. That is all. Chris Kelly’s highly personal and somewhat autobiographical dramedy recalls the period in his life when he had to take care of his mother through her battle with cancer. A carefully selected cast makes sure that the tragicomic range of human emotions is well-represented. It is the SNL and Broad City writer’s directorial debut, and stars Molly Shannnon, who is highlighted this year at SIFF.

Chris Kelly’s highly personal and somewhat autobiographical dramedy recalls the period in his life when he had to take care of his mother through her battle with cancer. A carefully selected cast makes sure that the tragicomic range of human emotions is well-represented. It is the SNL and Broad City writer’s directorial debut, and stars Molly Shannnon, who is highlighted this year at SIFF. Los Angeles has the largest population of Korean people outside of Korea, and that culture is well-represented by LA’s Koreatown, which houses restaurants, nightclubs, bars, and spas that recall the motherland well. Yet where Korean society may be somewhat reticent about addressing LGBTQ rights, Koreatown’s mix of American and Korean culture leads to first-generation Korean-Americans with far different takes on the issue. In Spa Night, uses a fantastic performance by Joe Seo to explore gay hookups in a traditionally conservative setting.

Los Angeles has the largest population of Korean people outside of Korea, and that culture is well-represented by LA’s Koreatown, which houses restaurants, nightclubs, bars, and spas that recall the motherland well. Yet where Korean society may be somewhat reticent about addressing LGBTQ rights, Koreatown’s mix of American and Korean culture leads to first-generation Korean-Americans with far different takes on the issue. In Spa Night, uses a fantastic performance by Joe Seo to explore gay hookups in a traditionally conservative setting.

Using a hand-held and conversational approach to shooting From This Day Forward, director Shannon Shattuck bares the soul of her entire family with seemingly little hesitation. Complex issues are implied; there are recollections of divorce that never came to fruition, and it is hinted again and again that her parents’ relationship is a constant “work in progress”. But they are also confronted head-on. Shannon and her sister lament the fact that Dad decided to “go full-time” when they were still too young to know who they themselves were, and they wonder why he insisted on being such an involved parent, despite how humiliating it was that he chaperoned school trips dressed as a woman.

Using a hand-held and conversational approach to shooting From This Day Forward, director Shannon Shattuck bares the soul of her entire family with seemingly little hesitation. Complex issues are implied; there are recollections of divorce that never came to fruition, and it is hinted again and again that her parents’ relationship is a constant “work in progress”. But they are also confronted head-on. Shannon and her sister lament the fact that Dad decided to “go full-time” when they were still too young to know who they themselves were, and they wonder why he insisted on being such an involved parent, despite how humiliating it was that he chaperoned school trips dressed as a woman. Finding Phong opens with raw, hand-held footage shot by Phong himself, who cries as he speaks to his mother in a video diary he hopes she will never see. Phong is only in his early teens and greatly loves his parents, but implicitly understands that his quest to become a woman is at odds with the desires of his immediate families Yet it seems that he, much like Trish, believes that fully embracing his womanhood is the only way to save himself from certain death.

Finding Phong opens with raw, hand-held footage shot by Phong himself, who cries as he speaks to his mother in a video diary he hopes she will never see. Phong is only in his early teens and greatly loves his parents, but implicitly understands that his quest to become a woman is at odds with the desires of his immediate families Yet it seems that he, much like Trish, believes that fully embracing his womanhood is the only way to save himself from certain death.

Photograph by Abe Mora

Photograph by Abe Mora