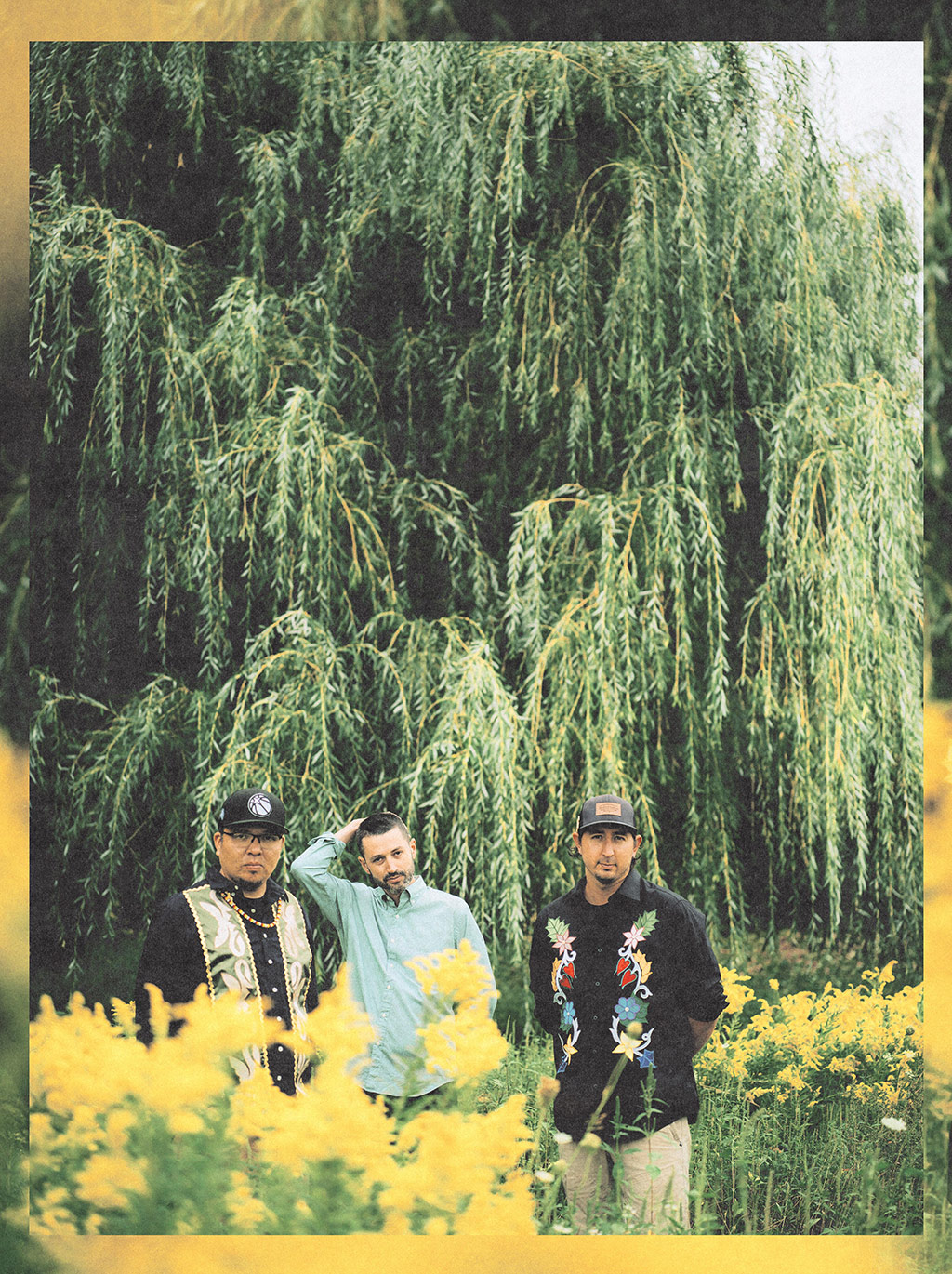

Film still from Milisuthando.

What were the initial kernels of inspiration for Milisuthando? Because I know you created it over the course of [nearly ten] years. What started it off initially, and how has it changed in this process?

Milisuthando Bongela (Filmmaker):

I’d say the first moment when I knew that there’s a story to be told, was when Nelson Mandela died in December [2013], and [my friends and I] went to the funeral and to the vigils outside his house… to pay our respects. And I just remember being there singing struggle songs with my friends.

And I’m singing along with everybody, but as I’m singing, I’m like, “It’s not true for me…” However, most Black South Africans… were extremely badly affected by apartheid. And I was like, I can’t really identify with the people in the song if I’m really honest with myself, and I felt a sense of shame.

I was like, “Wait, What does that mean? Am I allowed to be that Black person that didn’t have the worst experience?” And so, I was like, “Wait: where did I grow up?”

I realized that I grew up in another place that was the Transkei, but I didn’t really know what the Transkei was. I just knew that there was this kind of idyllic childhood that I had. I didn’t experience apartheid in the same way that people always talk about. But no one has ever framed that for me. And why and how? Because when you’re growing up in a particular world, there’s no questioning. It is what it is.

Map of the Transkei, produced by the CIA. From the Perry-Castaneda Map Collection.

That was kind of the first time where I was like, “There’s something here.” And then, the following month, I was out with a friend having breakfast… Instagram was just new, and we’d all just started making our accounts, and I remember being on Instagram and seeing all these gorgeous black girls with long, straight hair, and I was like, “Maybe I should straighten my hair, and maybe get a weave… because everyone looks so cute.” And I told my friend, and he kind of laughed it off. He was like, “It’s actually ridiculous. Why would you do that?” I was like, “I don’t know. It looks cute.”

And he just started talking about racism and identity and apartheid, and I was like, “What the hell do you mean? What does any of this got to do with my hairstyle?” And we kind of got into this argument, and I felt shamed, because I’d already made the booking at the salon, but I’m too ashamed to go. I’m like, “Is everyone gonna laugh at me? Is there something that he knows that I don’t know?”‘ And I went home, and I remember looking in the mirror and being like, “Yeah, I don’t love my hair, actually. I do want it to be straight. And why is our hair so hard?… Why are we like the wretched of the earth?”

And I knew that there was something deeper… God didn’t create me to hate myself. Something else must be going on. And I think I’ve typed in black hair and identity or something, and I fell into a rabbit hole…

So I interviewed some friends of mine, talking about their relationship with their hair, and it was so obvious that this was the site of so much personal and cultural struggle around who gets to be beautiful, and… how we accept ourselves. This is the way racism against colored people lives kind of, for free in our minds, all day long, especially as young people; as women.

[I] did a lot of research for about a year and a half, actually, [on just a] film about hair. I went to go pitch it in… 2017 at Durban, to [a person at] HotDocs… she was just like, “Yeah, you know, I see what you’re trying to do. I hear you, but the story has been told. And people are gonna learn anything new. What are you gonna do? What are you doing with it that we don’t already know?…”I was like, “She’s right. Let’s go deeper.” And it kind of changed from then on, where I was like, “Where did I learn to hate myself, because I didn’t hate myself.” And then it became a film about those Model C schools — those schools that we all went to in the ’90s after apartheid. I realized that very few people had done any extensive research on the experience of black children that went to those schools and how close-range racism functions and loops…

Our parents were all happy that we were in these schools — but we were too small to actually go home and say, “Wait, the racism is now sitting next to me at class; in the playground.” And then at the school… during lunchtime, you could just go and ask for these sweets called “n*gger balls.” Just, “Hey, can I have two n*gger balls, please.” Literally, we walked into that kind of situation.

But it was confusing, because there were also nice things happening. We were getting invited to sleepovers — but you go to a sleepover, and then, they wouldn’t touch your hair when they’re braiding each other’s hair or you go to a sleepover, and you can’t sleepover because your grandmother is a domestic worker, and you can’t get home the next day…

There was always slapping and stroking. A slap and a stroke is the experience I can describe it as — where you’re supposed to be grateful because you’re getting all this exposure or this education, or this privilege, which you are; it’s why I’m sitting there. But it came at the price of all these tiny daily cuts. And these forms of intimate, quiet violence deployed by the teachers, by the school, the actual building itself, your friends, their parents, the whole community that you walked into. And there’s no space to really articulate this trauma.

I think a part in the film that really stuck out to me was when you’re talking about the ways that your white teachers smile at you, but don’t really look at you. I think you summarize it very well.

Yeah. And so many people can relate to that thing, because we’ve all been experiencing it. But why does no one say anything about it?

It’s part of the power struggle. People are afraid to talk about it. Because I’ve had so many conversations with POC friends who are like: white women are like, worse than men sometimes, but it’s hard to articulate it because it’s more subtle.

That’s what makes it more violent. It’s the whole fallacy that it’s subtle. It’s not subtle. They are the ones that are most proximate to the white man. It’s their father; it’s their son, it’s your brother. They sleep next to them. And so, on one hand, they are subject to white men, but they also influence white men and the ways white men move, and… all of this rapacious activity that’s been happening all over the world since the last 5 to 7 years… the way it’s written about and talked about is for the sake of the white woman, and the white child.

It’s for her that we will kill a whole village of people because maybe she fell in the river and that village brought her back… so I felt that white femininity is much more nefarious as a thing that we’re dealing with…

Yesterday, when I showed it at AMC, a white South African woman was there, and she came up to me, and she did everything but talk about the film. She wanted to come talk to me. “Hi, I’m so and so. Living in Seattle. I’m so proud to see a film by black South African filmmaker.” Nothing about the story… so there’s this cognitive dissonance that will also occur, [which] I’ve experienced.

A white South African journalist — she’s a woman — interviewed me. She just wanted to talk about the fact that she watched the film, and all she could talk about was the fact that it premiered at Sundance and how glamorous that is but nothing about the actual film itself, which is about her as much as it is about me. I said the achievement is one tiny thing. What about the film? And she couldn’t access herself because there’s extreme cognitive dissonance where she knows it’s a critically good film, but does not know how to put herself [in it]…

For a long time, [Milisuthando] was about the schools and what they did to us, and how we changed them and transformed them, but how they transformed us. And just: this thing of like, our parents sending us into the hands of that lion, knowing what those would have done to them. What did that mean? What did that take? What did that mean for them? That must be complex. And when they look at us, they go, “Oh, we did nice; look, our kids are in America, working, making movies, getting awards.” But there’s a huge cost and price that we paid that they’re hardly talking about, because it’s not a big trauma. It’s not like, “Oh, I got raped or… I got beaten.” It’s much more benign…

I was in a state where I was just constantly upset… I was like, “How do I get out of this constant state of rage?” Because it’s affecting everything in my life, and I’m not born to be constantly rolling my eyes… and writing letters and being upset. There has to be more to my life than this.

What is it mean to identify and observe the wrongdoing or the racist side [with] your own wellness and your own sense of self as a person and as a spirit?… How do they coexist within you in harmony? This thing of you needing to observe and point out the problem, but in a way that doesn’t harm who you are, ultimately, and in a way that doesn’t replicate the very thing that you’re criticizing?

After a while, I went home to my grandmother’s house. I said, “I can’t be in [Johannesberg] anymore.” I’m tired. I’m just always angry, and I feel like this thing is also chasing me, because everywhere I go, some white person will just come to me and say some messed up thing, and I’m like, “What is going on?”

I’m at the movies, and I’m watching a movie, and after I watch the movie, two ladies come in, and say, “I’m sorry; have you finished cleaning the movie theater?”

No!

Yes.

So going to grandma’s was restorative?

Grandma’s was like: I need to get out of there. Where does grandma live? She lives in the Transkei… rural, maybe 1,000 kilometers [away]. You have to take a plane or drive for a long time. I was like: I’m out of here. And I just want to spend time with her, just doing nothing. To help her go to collect her pension, sweeping, cleaning, making food, walking around to the neighbors, visiting people… I started to calm down in a fundamental way.

First of all, this landscape? Yes. The way that people are; the language. I didn’t speak English — which I was like, whoa, wait. I don’t have to speak English… everyone only speaks Xhosa, and that language is not just conveying communication. There’s a whole knowledge system inside of it. I was like: but how do these people retain their dignity and their beauty?… They’re angry, but they’re angry in a very particular way — that almost hasn’t been whitened. That lactification hasn’t really happened. I’m experiencing a sense of self that’s different.

Not to romanticize anything, but… I was watching my grandmother. She lived through colonialism, apartheid, the Transkei, and democracy, all in one lifetime. How is she so joyful still? What is that? How? I just used to record her anyway, because I find her fascinating and the way she walks… how she repeats everything.

I was always already writing about and filming her, and I remember: after maybe 10 days of being there, feeling like there’s another place to who I am. There’s another life. There’s another story. My beginning is not inside whiteness. My beginning started here. And I became really interested in the history of the Transkei — and how, of course, my grandmother, every time you see her, she will mention that Mandela ruined the Transkei thing. Literally. This is her mantra.

And the only reason she mentions it is because she worked for the Transkei government for a long time as a teacher, and all her pensions? She lost them when the Transkei government ended — and so, she had to start from scratch in a new government. This is what pushed her and a whole bunch of other people off, like: these people ruined our pension. It will be: I’m going to collect the pension, and then she’ll mention, “Oh yeah, do remember that the pensions were lost in Transkei?” And then there’ll be a whole rant about Mandela and South Africa, and then my uncle will come over, and then they’ll have an argument. It’s very funny. Too bad that couldn’t fit in the film, because the arguments in them are totally hilarious.

That’s like its own short film.

I think I can make it into its own short film…

That then became the doorway through which I was interested in Indigenous history and knowledge. What was the Transkei? Who lived here? What are our belief systems as people who are from [there]?

I’m from another part of the country; my family only came in the 1830s — and so, I then met all these healers in that time. When I started asking those questions about Indigenous knowledge, I was just thrown into a world of healers, and people who were integrating Western knowledge systems, Western healing systems and African healing systems in their work. So literally: medical doctors who are also mudangs in the Korean sense, and sangomas in the South African sense…

When you get called to be a traditional healer, it’s not a choice; ancestors choose you, and they show you through various methods, either experience, or you’ll get… certain ailments and certain symptoms, and then you go to a healer, and they say, “Yep, your grandmother wants you to join the force,” or, “The great-grandmother wants you to join the force,” and you have to go to training.

And a lot of young people in the country, in different careers [are being initiated]. You can be an actuary, you can be an actor, you can be a lawyer, you can be a dancer, you can be a painter… Because I feel like this energy that was suppressed for 200 years because of certain laws that called it witchcraft is now emerging, because now, we’re free to move and become and express ourselves — and so, it also wants to be expressed.

I still talk to them. I’m still immersed in the healing methods and the healing modalities about people and how they understand psychology, how they understand art, how they understand the body, how they understand the spirit… then I had to include that element of that part of my journey.

It was the thing that was helping me deal; [to] continue to look at race and racism — because when you look too much, it’s hurtful. It’s painful. You don’t want to look. Why do I want to wake up and look at archives of the monsters? I don’t want to do that. But I also had to transform the way I saw this work. It wasn’t just my own egotistical looking at history. I knew this was something that people in South Africa needed to see. So how did I ensure that I’m looking with as much — not objectivity, but I have to process my own pain, so that I can try to understand what’s happening rather than look with eyes and fingers that are contaminated by my own rage.

Right. Because you mentioned researching and trying to understand the white perspective, and that shows up in your film through your friend. How did those conversations begin? It must be a friend that you trust to be able to get to that level, I imagine, of conversation.

I’ve known Marianne for a long time. We’ve always been able to talk about this at this level. But I myself was more interested in: how do I behave around [her]? How do I posture? If I’m scared of white people, how does it show up in my relationship with her, right? How do I exceptionalize her?

Because I used to have many white friends, and when I started the journey of making the film and writing about making the film and being kind of vocal about how this bullshit is still continuing, a lot of them scurried off. They weren’t trying to engage me, and they were denialists. We’re not friends anymore, and I’m okay with that. But the ones who stuck around, I was like, “Okay, so can I be myself around you?” And it’s very hard when you’re dealing with somebody that’s close. It’s much easier when someone is a co-worker or some stranger in the street. When there’s a lot to lose between the two of you, it’s very hard to go into that conversation.

I knew that I had to, at some point, be vulnerable and bare myself. Because first, I tried the whole life, while I’m the black person, and you’re the white person, and I’m gonna now interview you, and I know… that didn’t work, because it just didn’t produce the thing that I thought it was going to produce.

It took that moment in the hotel room to happen… for it to unravel, really, for me to be like, “Wait a minute, wait a minute. This is what I’m talking about.” I’m having this reaction where you just asked me to turn the music down, and I’m like rushing off, almost freaking killing myself, trying to quickly do it so that I’m not going to upset you. It became a long conversation about, “What does that mean?”

Yes, to you, you’re asking a normal simple question — but this is what it means to have proximity to black people of color, is that: we all hold these traumas, and they really come out in these spaces. It’s basically me saying: you have to engage your power. Whether you want it or not, whether you… acknowledge it or not, it’s there, and I’m having to engage my fear, which is not the thing we want to talk about.

[As Black people,] we always want to talk about how strong we are, and how much we can see, and we’re like, “Yes, don’t come at me.” We’re always having that energy, and I’m like: yes, it’s there, but also, there’s another energy that’s much more frightened, and is rightfully frightened, because when you upset white people, they can take away your resources. They can kill you; they can take away your land. There’s a historical reason to fear them.And so, what does it mean to have this friend who is all lovely and bubbly and friendly, and she’s like, “How can you be scared of me?” It was very hard. It’s very hard. But those are not easy [conversations]…

Ultimately, honestly, it did cost our friendship… It did affect it… I wouldn’t be want to say, “Oh, yeah, just do it, with your friend.” Because the things you discover about yourself; [the] things you discover about the other person in that space? You really have to have serious trust and maturity and courage to go there. And I think… we went as far as we could in that conversation, and yeah, it was difficult, but it’s exactly what I’m trying to articulate, and it’s one of those choices you make…

This is the power of representation, I guess. Media representation. Because I hadn’t seen that thing anywhere else in film. I didn’t see that conversation. It’s always Viola Davis and Julia Roberts being BFFs or whatever. That isn’t deep enough, and yet, all of this tension exists.

I don’t want to say it’s easy. We’re still navigating that thing, and it’s very painful, actually, especially now that the film is out… some of the reviews have not been the best in relation to Marian, and I’m like, I never wanted to… instrumentalize her. That wasn’t the point…

And I feel like showing clips of her with like friends — obviously, surrounded by black community, I think, also helped. It didn’t feel like you’re trying to demonize her.

Ultimately, I knew that I couldn’t do that. Because we walked down that road, and I was like, “This doesn’t feel good; this is not what I want to do.” In the process of learning how to film… my white friend, to have these conversations, was really a back and forth, and it required a lot of trust from her. Which she did ultimately give… though it wasn’t easy… it was always negotiation, which I understand.

That’s where I’m at. You gotta have proven yourself already. No educating..

If you’re not doing that work, forget about it. You can’t meet me where I’m going, and I can’t meet you where you’re going. And I don’t want to be in a position of educating; I want to be in a position of learning from each other…

I’m always looking for the ways in which it registers in white people’s bodies and gestures when they encounter me in the street, after the film, or even just in general. And that interest is the reason this film exists. Because my thing is: how many times are we going to keep explaining the same thing? Generations upon generations upon generations? Different types of people in different languages? When is this going to stop? Why does it persist? What happens in white families? When does the white child learn to look at a black person when they say the N word? A three-year-old? How does the three-year-old know, and [how] they are talking about me? No one is sat down and said, “Okay, here’s a spoon…” but somehow, the environment teaches that.

I am interested in racial conditioning within whiteness. That’s why the interest is more: I’m interviewing my friends, not my black friends. Because my black friends, you know their stories; you see it in their faces… we’ve all been saying the same thing… and I learned a lot from what Bettina said, for instance, because I had seen so many things about her family and her…

We were having tea at my house. We’re talking about our ancestors, and she was like, “Oh, yeah, my grandma great-grandmother came to South Africa to find a husband.” and I was like, “Oh, that’s quite specific… I thought she came to colonize…”

But no, a bunch of Irish women were being sent to South Africa to populate a landscape because these men had no women, because they were all very busy with the Indigenous women. But of course, that person had her own life; she had a reason to get on that ship. And all of them had their own lives and reasons to get on the ships. And so, when you allow nuance in, it’s not that it takes away the horror of the history, but I am trying to objectively make sense of: how does this persist? So that I know how to engage it at the source; so that I don’t frustrate myself, because I’ll frustrate myself if I keep saying, “I told you not to do that,” and it keeps happening.

[Inside] the Indigenous knowledge systems, the knowledge is very clear that we cannot rebuild the divisions. We cannot rely on separatism as a way of being. We have to figure out the true basis of our beliefs in Ubuntu. Which is the whole philosophy that fundamentally understands that we fathom ourselves through each other. So it’s not possible for me to know myself without engaging others, actually, unless I talk to you, and when I talk to you, I get an aspect of myself that’s different from when I talk to my grandmother, different from when I talk to my uncle, different when I talk to my boyfriend, to the cat, to the grocer, etc, etc. and that humanity is infinite. Your human personality and your mind is infinite — and you fathom yourself, and you collect yourself, through other people. And whatever it is you say about them, you’re actually saying about yourself, and vice versa.And so, what does it mean to not extend the philosophies of apartheid in the fight against it? And so, intimacy then becomes the antidote to fascism. And this is where things are most rough: is when things are here… I fundamentally believe that… we’re only going to resolve these things when we begin to really engage with each other, and that space is frightening for everyone, for different reasons. Because inside of it, we realize we need each other…

For me, the conversations with [Bettina] and the fact that I was like: well, I’m still building my relationship with you. These are the questions that I have for you, as my friend, as my neighbor, as a person I’m interested in, but also as a white woman. And the way she answered them, for me — the way she carries herself, the way she engages this — is so exemplary of what could be for so many people…

Some of the things she said, I really needed to hear. I didn’t realize how much I needed to hear them. And I also got to understand that they don’t necessarily have the answers. Even if… 100 of the smartest white people in the world, the richest, the most resourced: even if they got together, they still wouldn’t know how to figure this thing out. And they need us. That’s why she says: I need my black friends to help me; I also need other white friends. But also me, as a black person, I need to say these things to a white person.

Because there’s some perspective things they can never figure out, because they don’t consider what the experiences are.

Exactly, exactly. And there’s also some experience things that we don’t know, because we don’t experience them. Not to equivocate, but to say it’s a give and take. Another friend of mine, who was white, said when he watched the film, and she talked about the separation of the meat [between black and white people…] he remembered when he was eight years old, in Boston, at school… in the early ’80s, a black kid came to this white school that he was at, and the kids… did this thing in the class where nobody would want to touch the door handle if the black kid had been the last person to touch it. So they’d all kind of feel distracted or something towards them whenever they have to go open the door. And it’s those little things that will never make it to the news, but they exist in their memory.

And maybe not even til you brought it up in the film. Sometimes you forget about that stuff.

Exactly. And so, it’s all set up to kind of provoke these memories…

What is the significance of using your own name as the title?

I mean, I didn’t want to… but essentially, I am very much being propelled by the meaning of balance…

[My name] means bearer of love and peace, where there is none. And back where I come from, your name is your purpose. In many cultures, you don’t ever have to wake up and go, “What’s my purpose? What am I here for?” because it’s already given to them; built in your name…Hopefully, It’s visible in the film — that every frame is filled with love, even for the monsters.

I definitely feel that actually. Because I feel like you’re talking about some really hard things, but you’re not doing it in a way that It’s factual. and it’s like showing the truth, but It’s not like overly harsh or cruel.

Because I’m dealing with people and people. You can’t reach them. If you’re beating them.. you need to tell people how difficult it is while they’re sitting in a warm bed…

It wasn’t a brain film. It wasn’t intellectual [or] only intellect. It’s holistic. It’s physical, its memory. It’s psychological. It’s spiritual. And for me, honestly, the spirituality and going that route, and engaging my ancestors down to ideas that are in the field I got from them.

Yeah. Can we talk about that? What is your relationship to your ancestors and how did they show up?

I came from a home where I was born inside of this. Luckily, I never had to go discover it out there. My father… he was an author, and a lot of his stories revolved around the subject of personal lives. The villager goes to the city, and then when they get to the city, they become a drunk, and they beat their wife and they lose all their money… because their ancestors are unhappy with them. Because they didn’t leave home properly. They didn’t do this ritual.

All of his work is imbued, a lot of times with this idea that: yes, we have our lives; yes, we have our individuality to some degree, as free agents, but we live in harmony with our ancestors. And at each phase of life, you have to involve them, so that you get that protection. Our whole belief system is that we don’t really know who the great creator is. There are certain names to the creator, but we don’t attribute any qualities — no gender… It’s none of our business. We don’t really know. The only people who may know are the ones who have died, and who are maybe closer to what’s on the other side…

We don’t really believe in death, per se. The body perishes, but the spirit lives on, when a person is coming, and the person is born. They don’t look at that baby as like a brand new soul, and it’s like, “Okay, who is here? Who’s coming to see us”‘ and the baby is handed over to the ancestors… but there has to be a ritual that says, “Okay, this is medicine time. From this day forward, she is your responsibility you have to protect; you’ve got to make sure that her life goes well-protected from illness… from financial strife, from violence, etc.”

You do these rituals, virtually every now and then, to keep the relationship… you have to keep doing these things, to ensure that the ancestors are giving strength to help you… the more you give to them, the more they give to you. We were told that if you forget your ancestors, then they forget you. And so, it’s almost like you have this team that works with you, and it’s a team that is drawn to your spirit, your soul, your purpose, your cause, and they share gifts with you…

I’m very lucky that it was not foreign to me; I wasn’t born outside of it…

My last question is… I feel like so much of the narration that you provide is really poetic, really beautiful. I’m wondering about your process for writing some of those narratives.

I only wrote at night… during the day, I putter about and do this and that, but [my brain] too noisy. So I’ll take notes about what I’m seeing and thinking and feeling. I’ll take scribbles — the first iteration on a restaurant napkin, because I’m always sitting in a coffee shop or somewhere writing — and then that’ll turn into cell phone notes while I’m driving or something, and I have notebooks everywhere…

Inside that process, when I’m really writing, I try to get messages. In order to have certain dreams and to have certain sleep, I have to control what I’m eating, what I’m drinking, what I’m saying, who I’m spending my time with, what I’m consuming…

The process is trusting that the path will appear. That’s the process. There isn’t a strict, “Okay, wake up at 4am, and then I go for a run, and then I’ll have a cup of coffee, and then…” You try to do those things to buttress and support your mind attaching itself to these ideas and holding on to them, but really, when the rubber meets the road, it’s like a pure magic thing that’s different for everybody.

There’d be nights where I sat, and there’s nothing that happens, and I’m just scribbling and I’m drawing. Also, obviously, reading helps; reading different texts that then spark certain ideas, certain words. I am a very slow reader, and I read that I read multiple books at the same time. I’m not a one-book person, so I’ll be cross-referencing three or four texts at a time, and trying to find the relationship between these ideas and why am I so excited by this?

All the writing in the film — especially the poetic bits in-between… was some of the first things that I wrote and finished. And then we were like, “How are we going to build each of these universes?” Each of the five chapters actually revolves around those… we call them transcendental voices. That transcendental writing speaks to that. And those are all instances in my life. Those are things that have happened to me that I’m writing about in a poetic way, but I’m using the second person, so that the audience can also put themselves in my shoes.

It was a lot of trust and faith and knowing that it has to come out of me. And I mean, the one thing I became confident about was writing. When I started the process, I was not a filmmaker, right? I never made a film before. I don’t really know much about the technical aspects. I had to learn all that stuff. And there was always the imposter syndrome looking at me like this: “Hi, I’m here.” Constantly.

But the one thing that always swatted it away was my ability to write and express myself, and I knew that the power of the writing is not didactic, and it’s poetic. It has to be in a register of the poetry. It cannot be in prose. It can’t be prose dressed up as poetry. It had to be true poetry that is able to cut through anything, anywhere at all times. And that takes iterations. Sometimes you’ll get one line, but then the rest you do have to build.

And yeah, there has to be love, man. Ultimately. There has to be love. It has to be words that people want to hang around. You don’t want words that people run away from. You want people to be like, “Oh, I want to stick around and hang around the sentiment…”

And you have to have love for people… part of the process was an exercise in really ensuring that: this other thing, which was my name, was also embodied within the writing… It can’t just be dry words; the words have to be drenched in some kind of intention and love… constantly asking, “What is this force? And how does it express itself? How does it wish to express itself through us?”

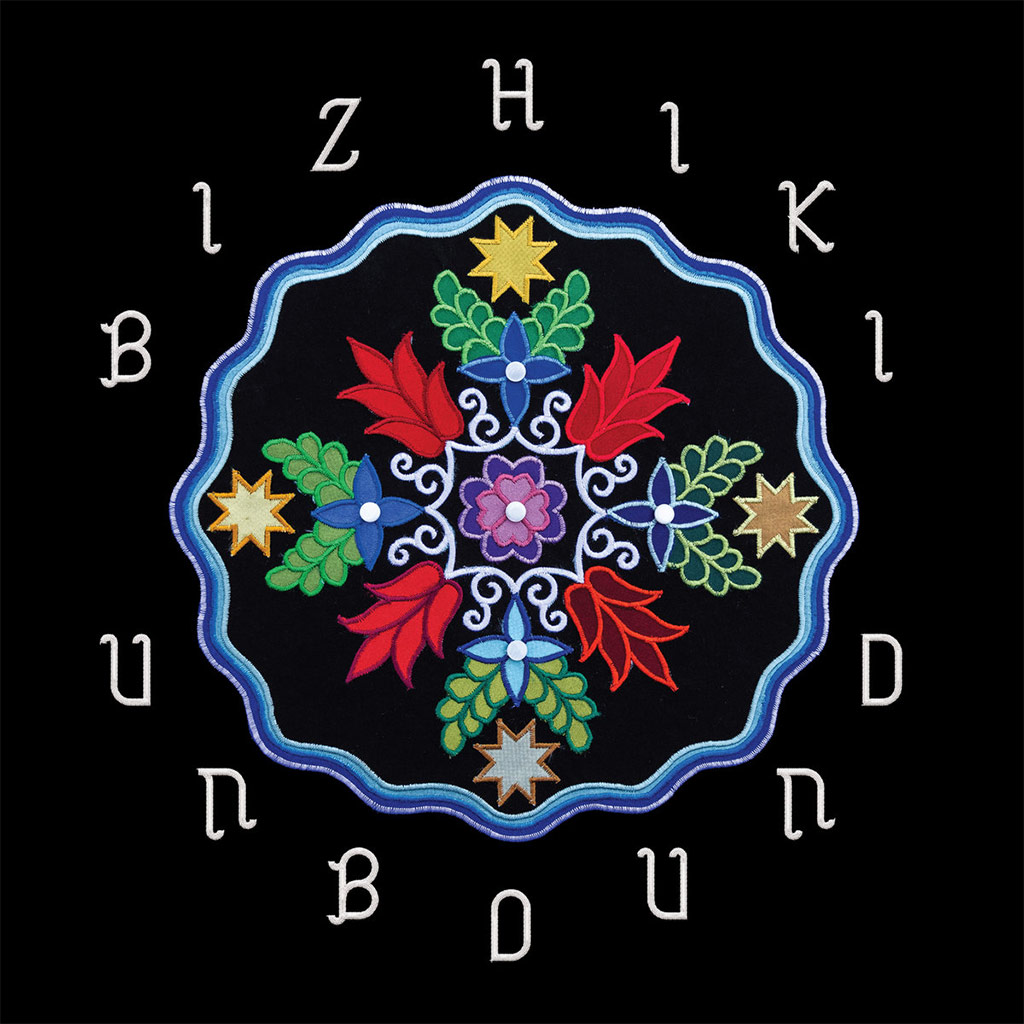

Milisuthando Film Trailer

Ω